SOUNDTRACK TO A COUP D’ETAT

SOUNDTRACK TO A COUP D’ETAT

SOUNDTRACK TO A COUP D’ETAT

France, Belgium, Netherlands

SYNOPSIS

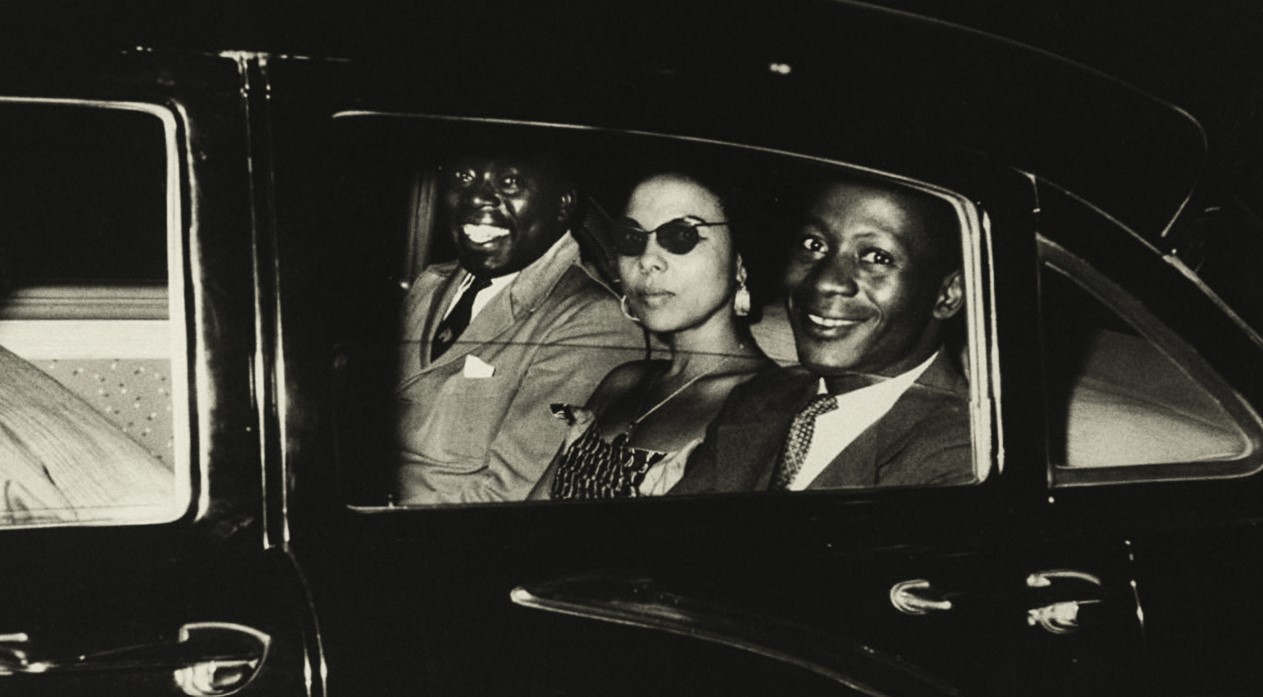

Jazz and decolonisation are entwined in this historical rollercoaster that rewrites the Cold War episode that led musicians Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach to crash the UN Security Council in protest against the murder of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba.

It is in 1960, six months after the admission of sixteen newly independent African countries to the UN, that a political earthquake shifts the majority vote from the colonial powers to the Global South. As Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev bangs his shoe in indignation at the UN’s complicity in the overthrow of Lumumba, the US State Department swings into action by sending jazz ambassador Louis Armstrong to Congo to deflect attention from the CIA-backed coup, featuring excerpts from ‘My Country, Africa’ by Andrée Blouin (narrated by Marie Daulne aka Zap Mama), ‘Congo Inc. ’ by In Koli Jean Bofane, ‘To Katanga and Back’ by Conor Cruise O’Brien (narrated by Patrick Cruise O’Brien), and audio memoirs by Nikita Khrushchev.

CREDITS

Written & directed by: Johan Grimonprez

Produced by: Daan Milius, Rémi Grellety

Cinematography: Jonathan Wannyn

Editing: Rik Chaubet

Sound: Ranko Pauković, Alek Goose, Florent Gailly, Céline Bernard, Maxime Chavepeyer

STATEMENT OF THE DIRECTOR

After my latest feature, SHADOW WORLD, which took me around the world to document the murky reality of the international arms trade, I felt it was time to dig into the shadow side of my own colonial past. Although it is now common knowledge that Belgium has been guilty of atrocities of historic proportions, the period surrounding the Congolese declaration of independence was still talked about in veiled terms. When we started our research eight years ago, it soon became clear that the events of 1960 mirror those of today.

As I immersed myself in the material, I came across several historical figures who, in the Belgian history books, had been labelled as villains. The more I learned about them, however, the clearer it became that they were not who we were led to believe.

One of the most important characters in this story is Andrée Blouin. Blouin, the daughter of a French father and a Banziri mother, was a passionate activist, gifted orator, and key advisor to the leaders of the emerging Pan-African movement. She believed a united Africa to be the best path to a truly independent Africa. She came to Congo to help with the election campaign of the Mouvement National Congolais, the Congolese National Movement, of Patrice Lumumba. Once there, she started a large emancipatory women’s movement, which, although women were not allowed to vote, contributed greatly to Lumumba’s popularity.

It is not surprising that the Belgian secret service tried to neutralise Blouin’s influence by portraying her as a communist, as the “courtesan” of the political leaders she advised, or even as a cunning femme fatale who was out to take every woman’s man. When these smear campaigns proved ineffective, and Lumumba’s victory became apparent, the Belgians expelled Blouin from the country, some days before independence. In her memoirs she explains how she managed to use her expulsion as a weapon in the fight against the treacherous regime: before boarding the plane, she hid a secret document in her chignon. On arrival in Europe, this document would prove that it was not Joseph Kasa Vubu (Belgium’s favoured candidate) but Lumumba who had the constitutional right to form the government. As a result, Belgium could no longer deny Lumumba’s election victory.

In the film, Blouin’s words, read by Belgian-Congolese musician Marie Daulne, better known as ‘Zap Mama’, represent the dream of a united, independent Africa. Throughout her life she was in close contact with many other African leaders, from Kwame Nkrumah to Ahmed Sékou-Touré, Modibo Keïta and Ahmed Ben Bella. After the coup against Lumumba’s government, she was again expelled from the country. She then spent some time in Algeria, after which she moved to Paris, where her house became a hub of the European Pan-African movement.

Another figure who is often differently portrayed than how I came to know him is Soviet chairman Nikita Khrushchev. The moment he demonstratively bangs his shoe against the table of the UN General Assembly is mostly presented as a proof of him being a brutish clown, a villain. I, however, came to see this act as a performative expression of his indignation at how the United States had corrupted the UN policy in Congo. In September of 1960, it was Khrushchev himself who asked the world leaders to come to the UN summit in New York to speak out together against colonisation. It was Khrushchev who called Dag Hammarskjöld a “lackey of the imperialists” after his double-dealing in Congo, which led to Lumumba’s downfall. Slamming his shoe, Khrushchev urged that the Swedish Secretary-General, whose family had invested in Congolese mines, be replaced by a “troika” of Secretary-Generals, each capable of representing what he saw as the three great power blocs: the Communists, the Capitalists and the Non-Aligned/neutral nations. Although it is usually pretended that this action had no consequences (the troika never materialised), it did set a lot of things in motion. For one, the anti-colonial resolution introduced by Khrushchev was subsequently ratified when it was re-submitted by an Afro-Asian coalition.

In 1956, just before Ghana was declared independent, Louis Armstrong played to a packed house in Accra for (among others) Kwame Nkrumah, the future president of Ghana. Four years later, Armstrong landed in Congo during a tour organised by the US State Department. His presence caused a spontaneous truce in the battle that was the result of Belgium’s attempt to regain control over its old colony. It was a battle that started only weeks after the independence ceremony. From Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) Armstrong travelled to Katanga to perform for the UN troops that had been installed there to help expel the Belgian soldiers. Recent research by British scholar Susan Williams revealed that Armstrong was used by the CIA as a Trojan horse in Katanga. During Armstrong’s visit, 1,500 tons of high-grade uranium lay above the ground in Katanga. As the CIA was afraid that the Soviet Union would find out, they used Armstrong’s concert as a cover to prepare the uranium transport to the US undetected. Nevertheless, Armstrong was not only the unwitting pawn of the American political agenda; there were moments when the great performer stopped smiling and spoke out: he refused to play for a segregated audience in South Africa and when the National Guard was sent to Little Rock, Arkansas, to prevent black students from entering, Armstrong cancelled his tour as jazz ambassador to Russia with the words “the government can go to hell.”

Mark Twain said “history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” Today, just as 60 years ago, people around the world are taking to the streets to challenge injustice and wrongdoing.

Meanwhile, the situation in eastern Congo has not changed a bit. The strings are still pulled by international mining conglomerates that have mercenaries on their payroll. Like 60 years ago, the competition between different superpowers is actively being transformed into fear, which is in turn used to justify criminal policies. One thing is clear: colonialism has never gone away; it only changed its jacket.

-

Documentary Film Selection 2024

Nomination European Documentary 2024

Nomination European Film 2024