_UNDERSCORE:

Turbulent Dreams

_UNDERSCORE:

Turbulent Dreams

100 Years of Armenian Cinema

by Sona Karapoghosyan

During the one hundred years of its existence, Armenian cinema has gone through different transformations and changes, presented many old and new narratives, and tried to stay up to date with the developments of world cinema while keeping its own storytelling idiosyncrasies – or even bringing these to the history of cinema.

The birth of Armenian cinema started with the establishment of HayFilm (ArmenFilm) in 1923, the first and main film production body of Soviet Armenia. The institution with an almost non-existent budget gathered Armenian film enthusiasts from different countries and became a place for creative work and artistic collaborations. Hamo Bek-Nazaryan, who is considered the founder of Armenian cinema, moved to Armenia and directed his first Armenian feature, NAMUS in 1925 which was followed by ZARE in 1926. Focused on the fragile position of a woman in society, ZARE was also a film about the Yezidi minority in Armenia – two socially and politically relevant topics that were not widely discussed in the cinema of the 1920s. The silent film was also filled with depictions of Yezidi traditions and rich cultural life.

In the silent era and afterwards, filmmakers were always looking for narratives in the rich heritage of Armenian literature. In 1934, Amasi Martirosyan directed GIKOR based on a famous short story by the Armenian writer and poet Hovhannes Tumanyan. The heartbreaking story follows a 10-year-old village boy whose poverty-stricken parents send him to the big city to work and to become “a man”. Filled with elements of social realism, the film highlights the economical polarisation within society and the social class discrimination that has not ceased from existing until now.

During WWII and in the following years, Armenian cinema was not very fruitful, and the limited sources were directed to the front. The situation changed in the 1950s with a flow of emerging and aspiring filmmakers who were exploring new genres, for example musicals and melodrama. In 1958 Yuri Yerznkyan and Laert Vagharshyan co-directed THE SONG OF THE FIRST LOVE, a musical drama about a talented artist who gets spoiled by fame and loses his wife. In addition to the moral premise and the songs that have become classics, the film also depicts the urbanisation and development of Yerevan, the capital of Armenia.

The 1960s marked the start of the New Wave that brought success to Armenian cinema both inside the Soviet Union and internationally. HELLO, IT’S ME (1965) by Frunze Dovlatyan portrays a famous physicist who loses his fiancé during the war. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1966, thus becoming the first Armenian feature film to be included in the prestigious festival. The film was covering much wider topics than the unrecoverable wounds of the war, such as technological development, importance of science and innovation.

This period of cinematic revival was also characterised by other remarkable directors, such as Henrik Malyan, Sergei Parajanov, Artavazd Peleshyan and others. In addition to his world-renown feature films, Sergei Parajanov directed a series of short films in Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine. One of them, HAKOB HOVNATANYAN (1967), was dedicated to the art of the Armenian portraitist. Henrik Malyan directed WE AND OUR MOUNTAINS (1969), a comedy about shepherds and their lost sheep, a film that mixes humour with criticism of pretentiousness and fake morality. The Armenian village was always one of the biggest inspirations for the artists, for example for another prominent director, Bagrat Hovhannisyan. In 1977, he directed AUTUMN SUN, exploring the challenges of life in the village from a female perspective.

The Armenian cinema and industry were not very favourable to female directors. The only department of HayFilm that had a considerable number of female artists working was the section of animation. For around a decade, these young and talented women created their own style and played a crucial role in the upbringing of the following generations. Lyudmila Sahakyants was one of them whose CONGREGATION OF MICE (1978) was a dark and excellent satire for the social and political situation, alas relevant until today.

Political conciseness, criticism and self-observation became central for the cinema of the following decade as the Soviet censorship started to soften. Young filmmakers, such as Harutyun Khachatryan, Suren Babayan, Vigen Chaldranyan started to look for new forms of storytelling, both in fiction and documentary films. Babayan directed THE EIGHTH DAY OF CREATION, a short film based on the works by Ray Bradbury, discussing alienation, loss and grief. In 1991, Harutyun Khachatryan directed RETURN TO THE PROMISED LAND, a documentary following a displaced Armenian family from Azerbaijan, trying to start their life anew in Armenia.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, the First Artsakh[1] war, the declining economic situation in the country – these all halted the filmmaking process for around a decade, but this period of challenges became a source of inspiration for the following generations of filmmakers. Mariya Saakyan, one of the first female directors of the Independence era made LIGHTHOUSE (2006) and ALAVERDI (I Am Going to Change My Name, 2012), tender portraits of young women searching for a sense of belonging in a country that keeps transforming. David Safarian directed 28:94 LOCAL TIME (2015) which was revisiting the dark past of the 1990s that was also full of the unbreakable sense of community, love and friendship.

During the last decade, co-production with Europe became more common for the Armenian film industry which had its impact on the landscape of cinema. Films made in collaboration with France, Germany, Lithuania, etc. eased the path for Armenian films to international festivals, which also helped to internationalise Armenian cinema. Most of these films are built around the same narratives which reflect the current socio-political state of the country. Some of these topics are the conflict of Artsakh[1], woman issues, migration and forced displacement. SHOULD THE WIND DROP (2020) by Nora Martirosyan metaphorically tells the story of a nation that is not allowed to fly and was included in the program of the Cannes Film Festival in 2020. TWIST (2020), a short film by the young female filmmaker Ovsanna Shekoyan, explores modern relationships in Armenia, publicly exposed but full of hidden secrets. 5 DREAMERS AND A HORSE (2022) by Vahagn Khachatryan and Aren Malakyan is a delicate portrait of three generations of Armenians who aspire to fulfil their dreams during yet another turbulent period in the country.

[1] Artsakh: The Republic of Artsakh was a de facto independent country, though closely connected with Armenia and predominantly Armenian-populated, its territory remained internationally recognised as part of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Partners:

Sona Karapoghosyan

Sona Karapoghosyan

Sona Karapoghosyan is a film critic and curator based in Yerevan, Armenia. In 2017, she joined the Golden Apricot International Film Festival as a program curator, and co-founded GAIFF Pro, the industry platform of the festival. In recent years, she managed and curated multiple film screenings and film-related projects in Armenia and abroad. A member of the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI), Sona regularly contributes to several local and international film publications.

Armine Shahbazyan

Armine Shahbazyan

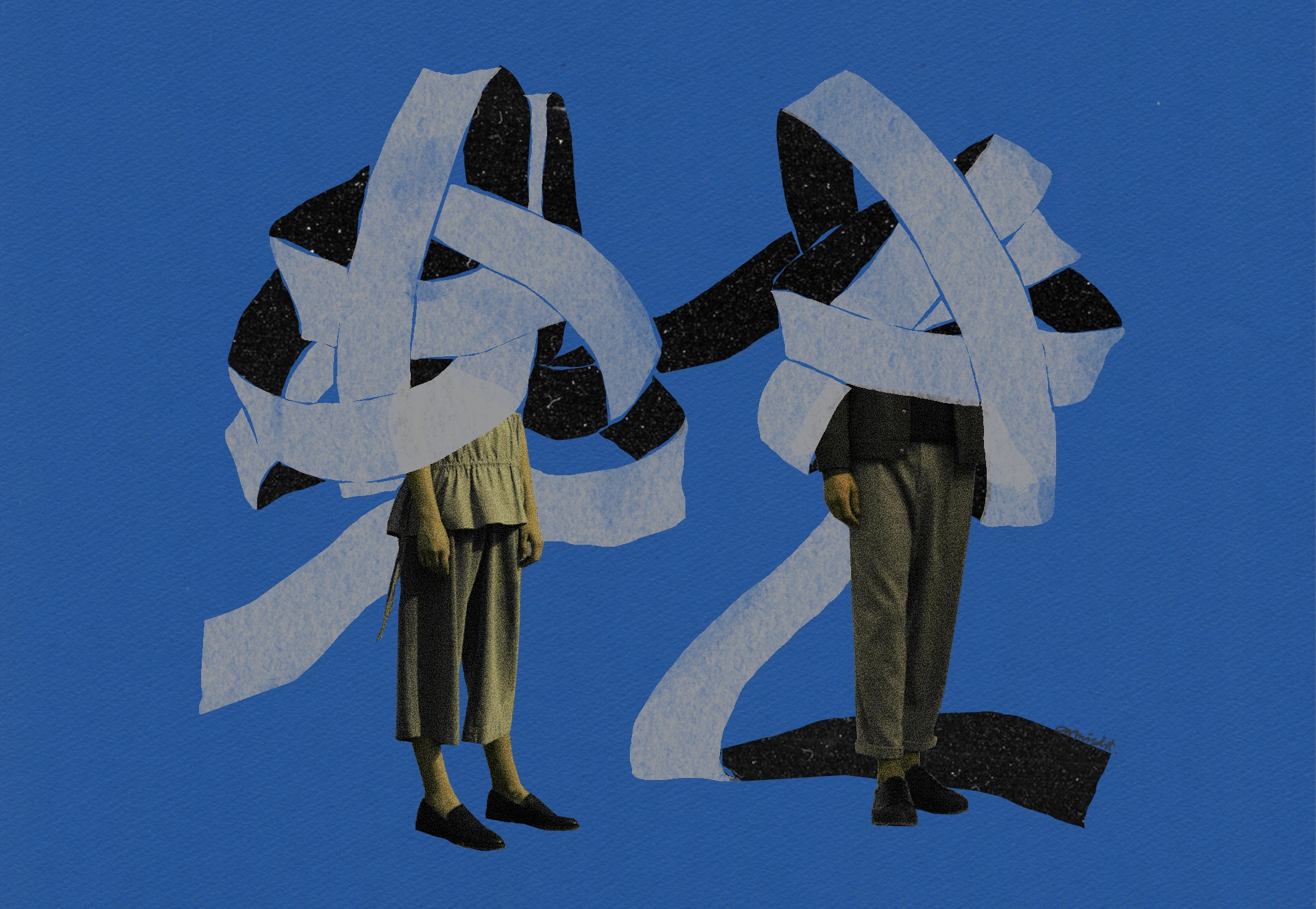

Armine Shahbazyan is an artist who transitioned from architecture to graphic design and illustration over eight years ago. She specialises in editorial illustrations and posters for films and theatres. Currently, she is an illustrator for EVN Report and works as the art director for the EVN Media Festival. She created the key visual for this edition of the _UNDERSCORE series.

National Cinema Center of Armenia

National Cinema Center of Armenia

Founded in 2006, the National Cinema Center of Armenia was established as an organisation targeted at the implementation of state cultural policy in the field of cinematography and a legal successor to Armenfilm studio. Today, the National Cinema Center of Armenia performs a number of functions i.e. providing financial support to local filmmakers, promoting national film heritage, presenting Armenian films in international film festivals and film markets.