DIVE INTO SWITZERLAND

DIVE INTO SWITZERLAND

BEING BERLIN - Part 1

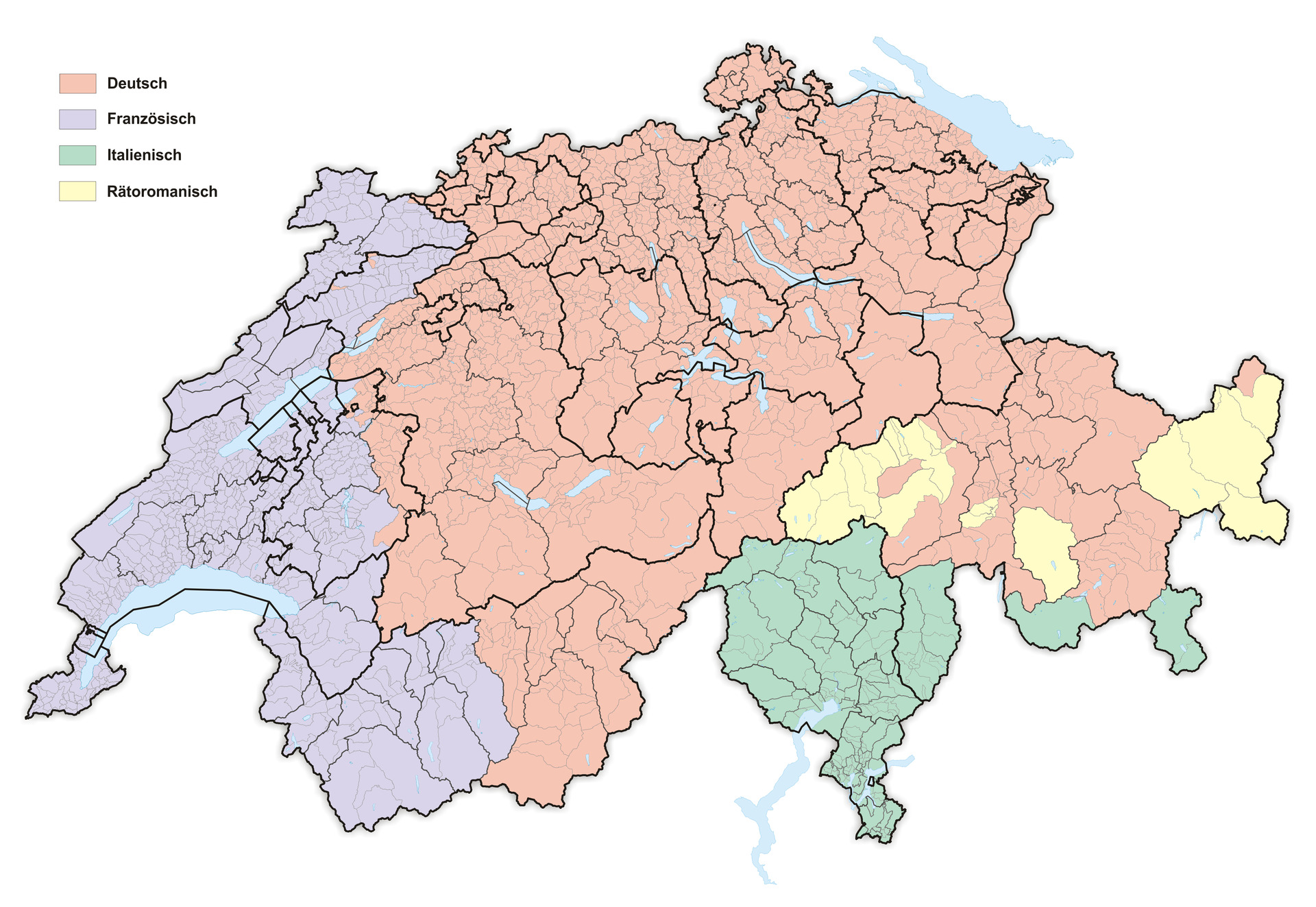

Bang in the mountains of central Europe, Switzerland is a small but varied country. Divided into 26 cantons, it has four official languages – French, German, Italian and Romansh (a kind of dialect of ancient Latin). Now, you might be forgiven for thinking that these languages are divided among the cantons in an orderly fashion but that is not the case.

Four cantons are officially multi-lingual: French and German in Berne/Bern, Fribourg/Freiburg, Valais/Wallis, and the city Bienne/Biel; and Romansh, Italian, and German in Grischun/Grigioni/Graubünden.

The so-called “Röstigraben” (literally, “Rösti trench”) also runs through the first three cantons. This marks the border between the predominantly francophone and German-speaking areas. This comes into play time and again in votes. The so-called “Polenta trench” in Ticino is less well known.

Why is that? And why does it still work? On the one hand, French-speaking Switzerland is more culturally oriented towards France, Ticino towards Italy, and German-speaking Switzerland towards Germany (the so called “Big Canton”), but on the other hand, the respective demarcation from the big neighbours leads to mutual rapprochement and a common destiny.

This is why Switzerland is not a “Staatsnation” (state-nation) like France, or a “Kulturnation” (cultural nation) like Germany, but a so-called “Willensnation” (nation of will): a voluntary community of resident citizens of different ethnic origins. With a strong federalist and direct-democratic political culture, and a government that does not have a president or chancellor in the usual sense, but a “Konkordanz-Regierung” (consociational government) in which the strongest parties are represented – more or less – according to their size.

The Fondue

Often considered THE national Swiss dish by foreigners and listed in the “Larousse Gastronomique” as a Genevan invention, the people from Neuchâtel believe the cheese fondue comes from their canton, but the Vauds and the Valais don’t necessarily agree. The word fondue has its origin in the French word “fondre”, which simply means “melted”. But don’t be wrong: it is not just “simple” to eat a fondue – there are quite some rights and wrongs about it!

Cheese fondue etiquette

KNOW YOUR VOCABULARY!

Caquelon: Cheese fondue pot made of cast iron, earthenware, ceramic or porcelain. The material should transfer the heat to the inside of the pot only slowly, so that the cheese melts better.

Rechaud: The stove on which the caquelon is placed, holding an open flame to keep the fondue hot, operated either with methylated spirits, gas or a special fuel paste.

Grossmutter (Grandma): The popular cheese crust that appears at the bottom of the fondue (provided it has been exercised in the correct manner …). Depending on the region, the crust is also known as crouton or la religieuse (the nun). Fondue beginners reveal themselves by referring to the crust as burnt cheese – In Switzerland, it is considered quite the opposite: This delicacy is so special that it must be shared.

Coupe du Milieu (shot in the middle): It’s a tradition to take a shot of Kirsch in the middle of the meal when your stomach is starting to feel full. Supposedly the shot rejuvenates your stomach and makes more room. Real connoisseurs don’t wait for the coupe, but every now and then bathe their bread cube in Kirsch before dipping it into the cheese – enjoying these “Schnapps pralines” (attention: this is not an official term!).

Moité Moité (half-half): There are hundreds of special fondue mixes, but one of the most well-known (and very delicious!) consists of 50% Vacherin Fribourg and 50% Gruyère.

When preparing your fondue, don’t forget to grate the caquelon with garlic. Leave the garlic clove(s) in the pan until the end – and enjoy after the meal (if you are not planning to meet with a vampire that night …)

Stir clockwise or in a figure-eight pattern to keep the cheese consistently melted.

Bread is what you dip into the cheese-wine-mixture. Tolerated besides bread are only potatoes, carrots or (only with very open-minded …) pears (legend has it that some people even put steak in it, as in “steak due”, but this is probably just an urban myth …). You can have pickled onions or cornichons on the side, but never (ever!) dip them into the cheese.

Twist your fork above the caquelon and pull to your own plate when the cheese string is fully wrapped around your fork.

Don’t dip at the same time as someone else. Taking turns in an orderly fashion is more appreciated, so everyone gets a chance to dip.

Whoever loses their bread in the cheese traditionally has to treat the dinner society with a bottle of wine. Alternatively, you can agree on another penalty.

Not all drinks are “allowed” at the fondue table: You drink white wine, Kirsch, herbal or black tea. Nothing else.

Never ever double dip: Once the bread has left the caquelon, it may never return!

Avoid smudging the dipping fork with your mouth. Gently remove the bread covered in melted cheese with the help of your teeth and lips from the fork without touching it.

Don’t double-fondue: No chocolate fondue as a dessert after the cheese fondue – this would not do anyone any good (not even if made with Swiss chocolate) …

With everyone stirring in the same pot, stay at home if you’re sick.

Chuchichäschtli and other linguistic specialties

«Säg emol ‹Chuchichäschtli›!» – It is not uncommon for non-Swiss German speakers to suddenly be asked by a Swiss person to say ‹Chuchichäschtli› (this refers to a kitchen cupboard) – an even better challenge might be the word ‹Abdröchdüechli› (staying in the kitchen, this refers to a tea towel). The word serves as a litmus test for Swiss German skills (and perhaps also for «integration»). The challenge is the many scratchy /x/ and /ʃ/ sounds, linguistically speaking, the voiceless uvular fricatives (although Arabic or Hebrew speakers have better pre-requisites).

The Swiss German dialects belong to the Alemannic language family or the West Upper German dialect continuum, which extends far into Alsace (Strasbourg), Baden-Wurttemberg (Stuttgart) and Bavarian Swabia (Augsburg). More precisely: to the High and High Valley Alemannic. Unlike in Germany, for example, where the standard German language has more and more replaced the dialects, in Switzerland the dialect is used primarily in almost all conversational situations. High German, also known as written German, is used in certain formal situations and in a multi-lingual environment.

Examples from the idiosyncratic vocabulary, which is also recorded by the Swiss Idiotikon (from the Greek idios, «separate, proper, private», as in idioms):

- If you are on a first-name basis, you also say Hoi! as a greeting (not to be confused with the English or Yiddish «Oi! »).

- The diminutive forms with the ending -li are well known: Müesli (Birchermüsli), Bünzli (Philistine, bourgeois), Rüebli (Carrot), Gipfeli (Croissant) etc.

- The latter is eaten for Zmorge (breakfast), the other meal times are called: Znüni (snack), Zmittag (lunch), Zvieri (tea time) and Znacht (dinner) – sometimes also Bettmümpfeli (bedtime snack).

- For Zmorge, there are croissants with Anke (butter) and Konfi (jam); for Zvieri, Käfele (have coffee together); and before Znacht, mainly at events, Cüpli (a glass of champagne) is drunk as an Apéro (cocktail party).

- Towards Berne, the vowels are getting longer and an «Äuä!» is interjected (probably not, «Really?!», you tell), or after long digressions a period is made with an «Item» (anyway) before getting down to business.

- With the colleague, who is not just a work colleague but can also be a buddy, we go to the Uusgang. «We’re going to the Ausgang» therefore means «We’re going out». The origin seems to lie in the nominative loving military lingo.

Incidentally, the past tense in Swiss German only exists in the perfect tense, (almost) never in the past perfect or past perfect tense. So, you never say «I went to Lucerne.», but with the past participle «Ech be uf Lozärn gange» («I did go to Lucerne.»)

Another peculiarity in multilingual Switzerland is the use of the so-called federal German or Français fédéral. In contrast to TV presenters, some politicians, even if they could speak perfect stage German or standard French, speak «extra», i.e. deliberately in High German and French with a Swiss accent, and like to use less eloquent, even downright wooden sentences (think of the cabaret artist Emil). In this way, they want to appear more likeable, «closer to the people». Because in German-speaking Switzerland, you don’t go down well with perfect High German or stage language, on the contrary: it can cause rejection or increase the distance to people.

The further west you travel in Switzerland, the more Gallicisms, i.e. French expressions, can be found in the dialects. Not because they are still à la mode. But because, as in other countries at the time of Louis XIV and Napoleon, the patricians, the rural gentry, oriented themselves towards the French court. That’s why we still say: Merci (thank you), Adieu (goodbye), Portemonnaie (wallet), Glacé (ice cream), Coiffeur (hairdresser), Billet (ticket) – but don’t forget to put the emphasis on the first syllable (unlike the «other» French who would probably put it on the second/last syllable …)

But there are also a few loan words from Switzerland. For example, (Bircher-) müesli or putsch. One of the best known – and yet little known – is probably the «Swiss disease» (lat. morbus helveticus) that was rampant among mercenaries at the time: homesickness. Some were even said to have died of it while abroad. Commanders therefore forbade the singing of certain folk songs, as these would trigger the disease and ultimately lead to desertion. Apparently, it was not until the Romantic period (19th century) that the term spread to other German-speaking countries.

Incidentally, the Lion Monument in Lucerne commemorates the Swiss Guards who fell in the Tuileries Storm. Swiss mercenaries in the service of foreign, also colonial powers were Switzerland’s first export hit. From what was then the poorhouse of Europe, locally one in ten of the country’s inhabitants hired themselves out as warriors. Many died, only a few patricians became rich.

Exploring Lucerne

At the end of the last part, we mentioned the Lion Monument, one of Lucerne’s most photographed “sights”. However, this monument also reveals that Lucerne — and with it Switzerland — has a colonial past with the mercenary trade, long-distance trade in colonial goods, banks and insurance companies for such enterprises, Jesuit missions, and tourism. The re-appraisal of this “colonialism without colonies” was initiated by the civil society, e.g. the association «Lucerne postcolonial» with the “Postcolonial City Tour”. A purely touristic exploration of the city, on the other hand, could look like this:

- You arrive in Lucerne on the SBB train as punctual as a Swiss watch and leave the station through the hall designed by Santiago Calatrava and inaugurated in 1991.

- As you leave, you will see the historic archway of the old railroad station, which burned down in 1971, with the sculpture “Zeitgeist” by the Swiss sculptor Richard Kissling, who also created a monument to Alfred Escher in Zurich, Wilhelm Tell in Altdorf and José Rizal in Manila.

- On the left, you will see the Reuss tributary and the medieval Chapel Bridge with its striking water tower. The bridge had 111 triangular paintings on its gables depicting important scenes from Swiss history before it fell victim to a fire in 1993, presumably caused by a cigarette.

- To the right, the Lucerne Culture and Convention Center (KKL) designed by Jean Nouvel with its exuberant roof occupies the space on the riverbank. It houses concert halls designed by acoustician Russell Johnson, for example for the annual Lucerne Festival, three restaurants and bars and the Lucerne Art Museum. And it’s the venue for this year’s European Film Awards Ceremony!

- Directly in front of you, you can see Lake Lucerne, which is bordered by five cantons (Uri, Schwyz, Obwalden, Nidwalden and Lucerne) and is also the reason why Lucerne is known by tourists as the “Riviera of Switzerland”.

- The panorama is dominated by the Rigi, the “Queen of the Mountains”, which has already captivated English tourists, including the painter William Turner, and of course Lucerne’s local mountain, the Pilatus, also known as the Dragon Mountain, whose summit has been accessible by the steepest cogwheel railroad since 1889.

- At the landing stage you can board, for example, the “Schiller”, the paddle steamer with a listed Art Nouveau saloon on which Alice Rohrwacher filmed scenes from “La Chimera” (2023) and which was recently included on the European Film Academy’s list of Treasures of European Film Culture.

- On the boat tour, you will pass Tribschen with theRichard Wagner Museum, where the composer once lived with Cosima Wagner; Bürgenstock, where the Ukraine Peace Conference took place; the Seenge Nas, so called because it looks like two noses, and which, as a fortified sea barrier during the Second World War, formed the entrance to the “Reduit”, the retreat area with military defence systems in the Swiss Alps in the event of an invasion; then the Rütli, where, according to myth, the oath of comrades to mutual assistance against the Habsburgs was sworn on the Rütli meadow, which is regarded as the foundation of the Old Swiss Confederacy – and where honoured speeches are still made today on 1 August, the national holiday. And after Flüelen, the Tellsplatte (and the associated chapel), where, also according to the myth, William Tell saved himself from Gessler’s captivity and the storm, before committing tyrannicide in the Hohle Gasse.

- You get off at the Museum of Transport, which still embodies the spirit of optimism about progress and, before digitization, housed an IMAX cinema with the largest screen in Switzerland.

- You stroll along Carl-Spitteler-Quai, which is dedicated to Switzerland’s only Nobel Prize winner for literature, past the grand hotels that bear witness to the heyday of 19th century tourism, when Lucerne developed from a small medieval town into a modern tourist stronghold – along with the nowadays global problem of “overtourism”.

- You then turn right towards the Bourbaki Cinema, which also houses the stattkino – both are partner cinemas for the Month of European Film and will present academy screenings with the honorary award recipients. The building is also home of the Bourbaki Panorama, one of the few giant circular paintings from the 19th century still preserved in the world. Edouard Castre’s panorama from 1881 commemorates the internment of 87,000 French soldiers who found refuge in Switzerland at the end of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 in the winter of 1871 – an indictment of the war and a testimony to the first humanitarian actions of the Red Cross.

- The tour then continues to the aforementioned Lion Monument, which was even visited by a delegation accompanied by bodyguards during the Bürgenstock Conference in June. Next to it is the recently rebuilt Glacier Garden, a natural monument that is highly topical, especially in times of dying glaciers.

- You then stroll through the old town until you reach the Spreuerbrücke, another medieval wooden bridge with a painted Danse Macabre. On Tuesdays and Saturdays, the well-attended weekly market takes place around the mouth of the Reuss. And during the Fifth Season, 2025 between 27 February and 4 March, the Fasnacht or Carnival.

- In addition to those already mentioned, there are cultural attractions such as the Neubad, a former indoor swimming pool, which also hosts the Filmtech trade fair, the Südpol, or the Lucerne Theater and the Rosengart Collection.

What to Eat

It is, of course, unlikely that you would want to interrupt your fondue diet but in case you have to, here are a few more Swiss specialties worth tasting:

Papet Vaudois

A leeks and potato mash with a fatty sausage. For those who need it or in case you were about to carry a cow up the hill or build a house.

Rösti

Thinly grated potatoes, panfried until crisp and golden and simply delicious. (look at the photo above)

Basel-style roasted flour soup

simply flour, butter, onion and beef stock, topped with a reserved grating of Gruyère. Legend has it the soup was created when a distracted cook was chatting away, leaving flour cooking in a pot until it accidentally browned. Rather than ditch the mishap, it was turned into a dish that has endured. The soup is a must-have at Basel Carnival, which is officially launched with a serving of it at 3am.

Raclette

Raclette is a local Valais cheese customarily grilled slowly over a fire, with layer-by-melted-layer sliced off to blanket boiled potatoes, pickles and onions. Contemporary raclette machines make grilling commonplace in Swiss homes, where friends gather for hours, waiting for slices of raclette to melt, while drinking copious glasses of local Fendant wine. It’s also a great dish to keep the kids busy and excited about the meal!

Polenta and braised beef

The Italian-speaking canton of Ticino has been stirring polenta – a cornmeal dish, cooked into porridge – for centuries.

Zürcher Geschnetzeltes

Zurich-style diced veal is an iconic national dish that makes a hearty, wintertime lunch.

Tartiflette

A staple dish at most ski resorts, Tartiflette is a starchy combination of thinly sliced potatoes, smoky bits of bacon, caramelised onions and oozy, nutty, creamy Reblochon cheese.

Chocolate, chocolate and chocolate

Just try them all: Frey, Lindt & Sprüngli and Cailler (attention – owned by Nestlé) from the supermarket and Läderach, Bachmann and Sprüngli from the special shops.

Where to eat out

Culinary recommendations include the Drei Könige, Magid Beiz, Maihöfli or the Jazzkantine as well as Glou Glou and the vegan Bayts in the Neustadt, the New Town on the other side of the Reuss.

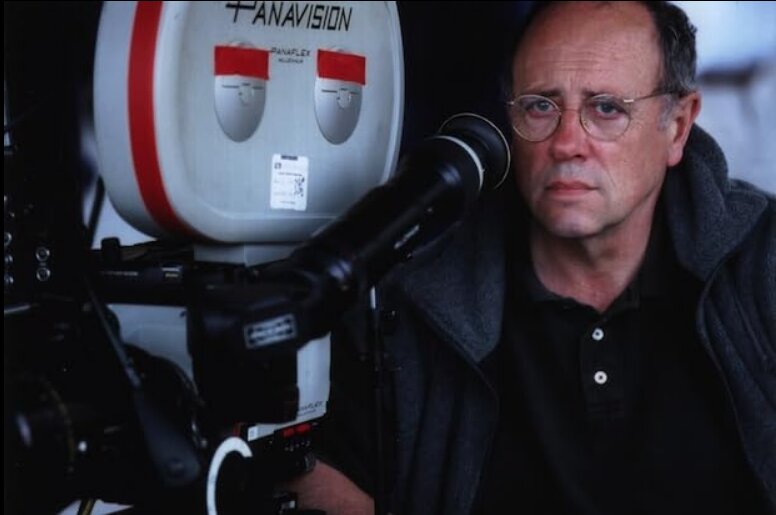

A Journey through Swiss Film

On the occasion of this year’s European Film Awards in Lucerne, our friends at the Cinémathèque suisse and SWISS FILMS have put together a list of recommended films:

Fiction films:

THE VILLAGE (Unser Dorf) by Leopold Lindtberg (1953) with John Justin, Eva Dahlbeck, Mary Hinton.

In a village created for children in the heart of the Swiss mountains, WWII orphans from all over Europe have found a home. The names “father” and “mother” are used in each house to designate their fellow countrymen and women educators.

CHARLES, MORT OU VIF by Alain Tanner (1969) with François Simon.

The film paints the portrait of an old man who decides to abandon his comfortable bourgeois way of life and live with a Bohemian couple. There he rediscovers his freedom to think and his joie de vivre.

LA PALOMA by Daniel Schmid (1974) with Ingrid Caven, Bulle Ogier, Peter Kern.

Nightclub singer La Paloma succumbs to the persistent courting of a chubby rich admirer and marries him. Before the marriage, she was thought to be dying, but soon she is well. She believes her husband’s love has cured her, but her efforts to love him begin to fade as she discovers true love with her husband’s old school friend.

L’INCONNU DE SHANDIGOR by Jean-Louis Roy (1967) with Daniel Emilfork, Jacques Dufilho, Serge Gainsbourg, Marie France Boyer, Ben Carruthers.

The interest of three rival groups – the Soviets, the Americans and … “The Bald Heads” – has been aroused by the Canceler, a machine developed by scientist Herbert von Krantz which is capable of defusing nuclear forces.

THUNDER (Foudre) by Carmen Jaquier.

Summer 1900, in a valley in southern Switzerland. Elisabeth is seventeen years old and about to take her vows when the sudden death of her older sister forces her to leave the convent and return to the family farm she had left five years earlier.

UINREST(Unrueh) by Cyril Schäublin

New technologies are transforming a 19th-century watchmaking town in Switzerland. Josephine, a young factory worker, produces the unrest wheel, swinging in the heart of the mechanical watch.

THE FAM (La Mif) by Frédéric Baillif

A group of teenage girls have been placed in a residential care home with social workers. This forced “family” experience creates unexpected tensions and intimacies.

Documentaries:

DANI, MICHI, RENATO UND MAX by Richard Dindo (1987)

A three-part documentary about four young men who were active members of the Zurich youth movement in the early 1980s and died tragically as a result of “accidents” with the involvement of the police.

TOSCA’S KISS(Il Bacio di Tosca) by Daniel Schmid (1984)

Giuseppe Verdi’s «finest work», as he himself described it, still stands today on the Piazza Buonarroti in Milan. It is the «Casa di riposo», founded by Verdi in 1896 for «people who are less fortunate than I» – people who never made a big career, and people who have long spent their dream salaries. Today they live, all long forgotten, in a small room with a suitcase full of memories.

THE HEARING (Die Anhörung) by Lisa Gerig

Four rejected asylum seekers relive the hearing on their reasons for fleeing their home countries, shedding light on the core of the asylum procedure.

WINTER NOMADS (Hiver Nomade) by Manuel von Stürler

Carole and Pascal leave for their winter migration with three donkeys, four dogs and a flock of sheep: three months of braving cold and snow.

Animation:

SAVAGES by Claude Barras

In Borneo, Kéria takes in a baby orangutan found on the palm oil plantation where her father works.

Short Films:

ALL CATS ARE GREY IN THE DARK by Lasse Linder

He calls himself Catman. Christian lives with his two cats Marmelade and Katjuscha. They are inseparable.

AND THE WIND WEEPS by Aulona Selmani

Daut, a survivor of a massacre where his son was killed, has been rehearsing a letter for twenty years on what he will say if The Hague ever calls him to testify for the horrors he has seen that day.

Reading Swiss

Arguably the most famous piece of Swiss literature, at least for German-speakers, is “Heidi” by Johanna Spyri, the story of an orphan girl who lives in the Alps with her grandpa.

Among classic authors of Swiss literature are Jeremias Gotthelf whose short novel “The Black Spider” (Die schwarze Spinne), tells a semi-allegorical tale of the Plague in form of the monster that devastates a Swiss valley community, as well as Gottfried Keller who is most known for his novel “Green Henry” (Der grüne Heinrich), a huge work drawing on Keller’s youth and career (or more precisely non-career) as a painter.

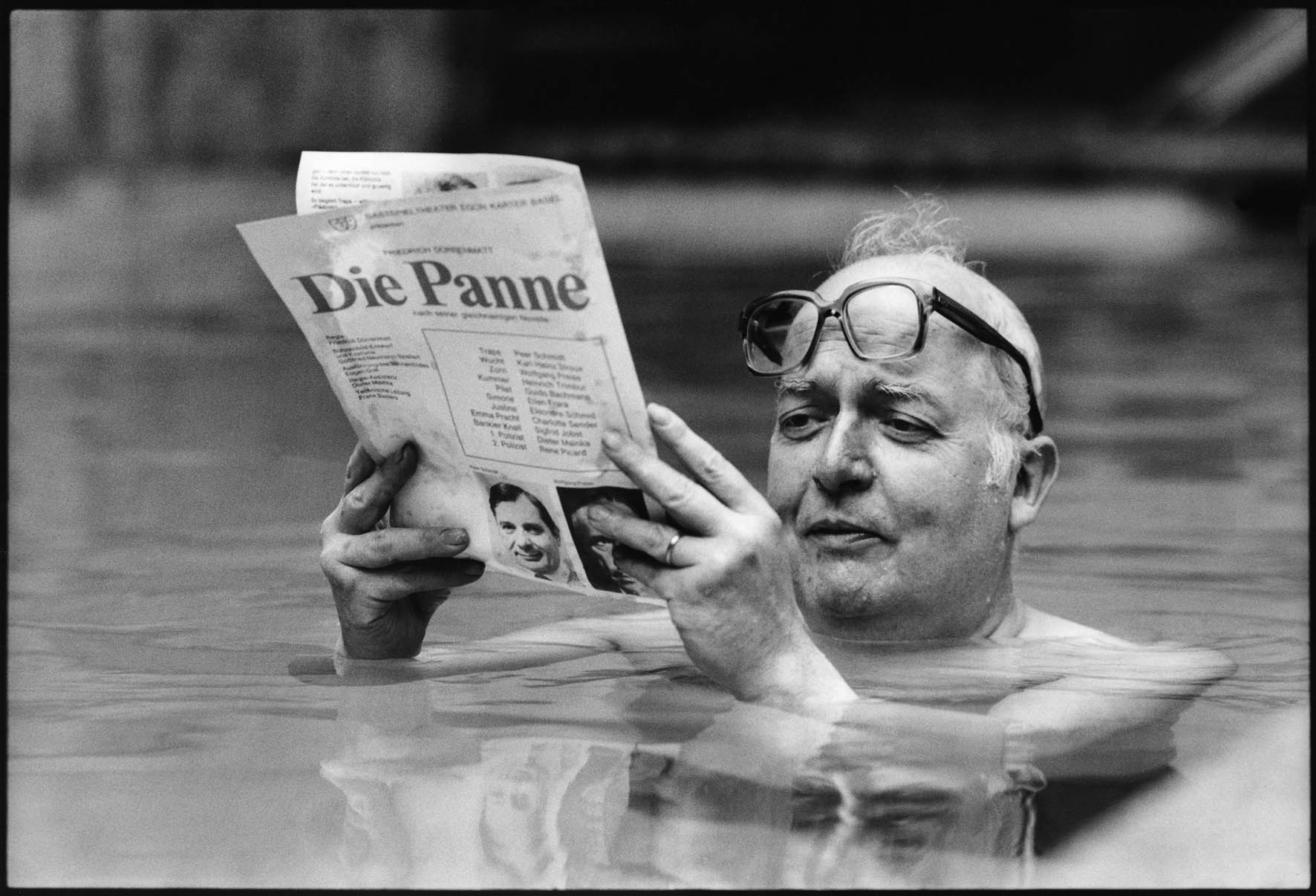

Later writers are Max Frisch whose “Homo Faber” has been translated into 25 languages and adapted for the cinema by Volker Schlöndorff. Friedrich Dürrenmatt is most known for “The Judge and his Hangman” in which inspector Bärlach must solve the murder of his best officer and “The Visit” (Der Besuch der alten Dame), a tragic comedy about a wealthy woman who offers the people of her hometown a fortune if they avenge the wrongs done to her.

Famous French-speaking writers were Jean-Jacques Rousseau (“Discourse on Inequality”), Blaise Cendrars (“Sutter’s Gold”) and Alice Rivaz (“L’Alphabet du matin“).

And among the contemporaries are Zoë Jenny („The Pollen Room“), Melinda Nadj Abonji (“Fly Away, Pigeon”) who deals with issues like migration, identity and belonging, and Joël Dicker (“The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair”), world-famous for his crime novels and thrillers.

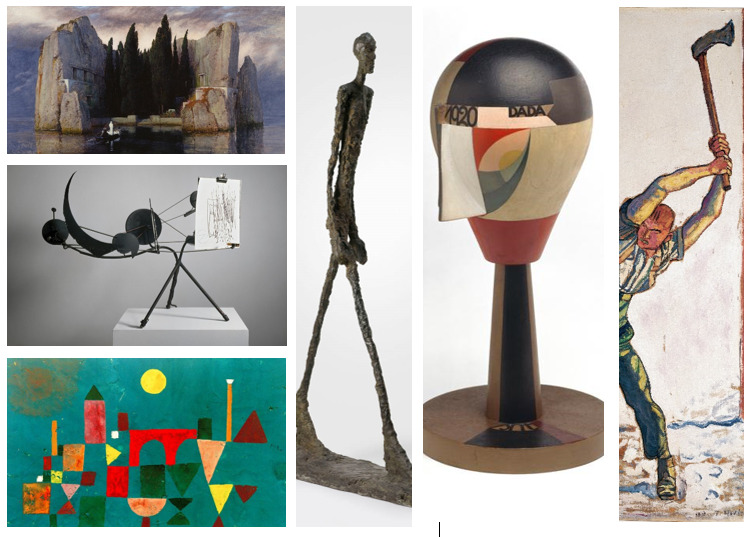

A Few Swiss Artists

A perfectly random selection of some of the greatest Swiss artists of all time might include Arnold Böcklin, Alberto Giacometti, Ferdinand Hodler, Paul Klee, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Tinguely.

One of the best known Swiss painters of the 19th century is Ferdinand Hodler who started out with realistic portraits, landscapes, and genre paintings, and later adopted a highly symbolic style of his own which he called “parallelism”.

Another Swiss Symbolist painter was Arnold Böcklin. His cycle of five versions of the “Isle of the Dead” inspired works by several late-Romantic composers and is considered iconic.

Born in Davos, Sophie Taeuber-Arp worked with geometric patterns and tried to integrate abstract art into our daily life. In 1918 she made her first Dada heads which became her best-known works and a manifesto of the dada movement.

The sculptor Jean Tinguely extended Dada into the later part of the 20th century and is best known for his kinetic art sculptural machines (known as “Métamatics”).

Fascinated by colour theory, Paul Klee developped a highly individual and unique style. Often playing with geometric forms, his works reflect his dry humor and his sometimes childlike perspective. The Rosengart Collection in Lucerne offers a great selection of his work.

Alberto Giacometti was a Swiss sculptor, painter, draftsman and printmaker, best known for his metal sculptures of thin-legged men on a stroll.

If you don’t find the time to visit museums, maybe you can buy a postcard. Or come back.

What to bring back

A SWISS WATCH

Famous throughout the world, the tradition and craft of watchmaking in Switzerland is legendary.* But you will never have an excuse for being late again.

CHOCOLATE

depending on how much you like friends and family at home (or yourself), you can choose between either Frey, Lindt & Sprüngli and Cailler from the supermarket or Läderach, Bachmann and Sprüngli from their respective individual store. Don’t miss out on the Grand Cru and the Truffes du Jour at Sprüngli (and the Luxemburgerli, even though they are macarons). There are plenty of stores around!

A SWISS ARMY KNIFE

The Swiss Army knife typically has a drop-point main blade plus various other blades and tools, such as a screwdriver, a can opener, a saw blade, a pair of scissors, etc. There are different brands, most famous is probably the red Victorinox kind with the Swiss cross on it – it is also available in all colours of the rainbow. Have your name engraved on the spot to personalise your very own Victorinox!

CHEESE

How could you return from Switzerland and NOT bring back cheese? Even the Gruyère from a Swiss supermarket is so much better than most cheeses you can purchase elsewhere. The good news: Most shops (and even market stands) will gladly vacuum seal their cheese for you so that your knickers won’t forever smell of Appenzeller and impede future romantic ambition.

MUESLI BOWLS or EGG CUPS

The traditional ‘Tüpfli’ pattern is handmade in Switzerland and looks great on any breakfast table. The typical polka dots are not painted on, but rather dabbed onto the base colour from a height of about 20cm using a pastry bag, which requires utmost concentration.

FONDUE FORKS

Take home a set of Swiss fondue forks, with the handles painted in different colours or in plain wood, or with panoramic views of Switzerland’s mountains – they will bring the Swiss mountains to your caquelon.

JASS CARDS

With an estimated 3 million regular players, Jass is so popular that it is often considered Switzerland’s national card game. There is a German and a French deck, each contains 36 cards in 4 suits and rumour has it that there are over 70 variants of the game, each with a different name.

A PINE BOWL

A handmade bowl of Swiss stone (Arvenschale) pine brings a very special piece of the Engadine to your home.

A SBRINZ KNIFE

Like Parmesan, Sbrinz is a very hard cheese and difficult to cut with a regular knife. With a special stainless-steel knife, you can easily break off bits and serve them as a delicious appetiser.

A Little Swiss Cheesology

EMMENTALER

Made from raw cow milk, Emmental cheese is one of the most recognizable cheeses in the world because of its large “eyes” which develop during maturation. It has a savory but mild taste and comes in wheels of a colossal size (diry farmers used to be taxed per wheel, not total weight). This is probably the most kids-friendly Swiss cheese, if there is such a thing.

GRUYÈRE

Originating from the cantons of Fribourg, Vaud, Neuchâtel, Jura, and Berne, Gruyère is the favourite cheese of the Swiss. It is a hard cheese that tastes seet yet slightly salty, creamy and nutty when young, more earthy and strong as it matures.

Gruyère is a good cheese for baking, traditionally used in French onion soup and croque-monsieur, good with Riesling.

SBRINZ

Sbrinz is a very hard cheese produced in Central Switzerland. Traditionally, Sbrinz is never cut, but grated, broken with a special cutter or planed. It is perfect for nibbling on or shredding on pasta or a casserole.

APPENZELLER

A hard cow’s-milk cheese produced in the Appenzellerland region of northeast Switzerland, Appenzeller acquires its characteristic taste from a herbal brine, sometimes incorporating wine or cider, which is applied to the wheels of cheese while they cure. The recipe for the brine remains a secret. You may want to avoid touching the rind. Or you will regret it.

RACLETTE

Raclette du Valais is a semi-hard cheese that is usually fashioned into a wheel of about 6 kg. It is best known for making the dish also called raclette, and has been used for the famous melted cheese dish since the 16th century. Both names derive from the French verb ‘racler’, which means ‘to scrape’, referring to the practice of melting half-wheels of cheese over fire, then scraping the hot cheese over boiled potatoes, charcuterie, and bread.

TÊTE DE MOINE

A semi-hard cheese, invented by the monks of the abbey of Bellelay. Unlike most other cheeses, Tête de Moine is cut horizontally instead of into wedges. The reason for this unusual portioning? The girolle, a device to help get the most flavour and texture from this particular cheese. The wheel is impaled on a central spike, securing it firmly. Then a handled blade is gently spun across the surface of the cheese, scraping up a thin layer of cheese and rind into a bundle resembling the petals of a flower.

VACHERIN MONT-D’OR

For most of the year, the milk produced by the cows in the Vallée de Joux of Vaud is used to make Gruyère. As summer winds down, the animals produce less milk, however, and can’t meet the needs of making the large wheels required of this famous cheese. The significantly richer, fattier quality of this late-season milk is perfect for making one of Switzerland’s most beloved cheeses, Vacherin Mont-d’Or. These much smaller wheels can only be produced from mid-August through the end of March, and are only sold from September through April.

Fully-matured wheels of Vacherin Mont-d’Or are an amazing experience. The deep, reddish rind is easily removed to expose the pudding-like interior. Rich aromas of bacon fat, cream, and spruce wood lead to meaty flavors and a sublimely smooth texture. For a truly outstanding experience, keep the cheese in its spruce container and heat in the oven until aromatic and soft to the touch. Peel back the top rind and dip bread, sausages, or vegetables in the gooey interior!