30 Years of “Post-Soviet” Cinema

30 Years of “Post-Soviet” Cinema

A thought-provoking list

On 26 December 1991, the Soviet Union was officially dissolved and ceased to exist. Not only in what were up-to-then Soviet states, but in large parts of modern-day Europe, this meant the end of a defining era. An era of direct or indirect communist rule, in all its forms and manifestations, and the different impact all this had on every aspect of life, from intellectual thinking to the mundane conditions of everyday life.

30 years later the European Film Academy together with goEast – Festival of Central and Eastern European Film want to shine a spotlight on the 3 decades of cinema following this defining moment in history.

They invited a working group of film experts from the region to establish a list of 30 works of cinema representative for this transitional period. Five experts accepted our invitation to participate in this challenging endeavor with an uncertain outcome. As a matter of fact, we were all acutely aware of the impossibility of this task and to make things even worse, none of the participants particularly likes lists or canons. The result is not a canon – it is merely an invitation. An invitation to discover works from Central and Eastern Europe that have received less attention than they deserve as well as encouragement to rediscover classics. It is also an invitation for everybody to add titles, to dispute titles and to argue about the terms “post-Soviet”, and “post-socialist”, especially in the context of cinema. Because, really, the main goal of our flawed, but hopefully thought-provoking list is to draw wider attention to cinema from Central and (South-) Eastern Europe in the years to come.

As some of you might have noticed with dismay, big names like Andrzej Wajda, Kira Muratova or Otar Iosseliani are missing from this selection of works. Experimental films and a surrealist short animation find themselves alongside classical works of fiction and documentary. Recent films from the past four years are missing altogether. Not because the level of filmmaking was lower – no, rather we found it impossible to judge more recent films within the greater framework of history and time.

Which are the films which provide a great introduction to three decades of post-communism? Which changes in society are visible in cinema from the region? Which events were reflected in remarkable films made in the past 30 years and in cinematic language from this part of Europe overall? Those were some of the questions the working group focused on, while at the same time being aware that certain highly acute topics were still missing or underrepresented.

Back in 1919, the first film academy worldwide was founded in Moscow. The medium of film has, to a large extent, developed alongside, in opposition to, but also within the ideological frameworks of communism in the 20th century.

Now, in the year 2021, we invite you to explore, comment on and share the titles on this list from the past 30 years, while the countries and film cultures in Central and Eastern Europe enter another era.

It is hard to predict with certainty what that era will bring, what name it will have and what its characteristics will be. One thing is clear however: The collapse of the Soviet Union and the so-called Eastern Block were the end of an era – but certainly not the end of original and surprising cinema.

The Films

THE DEATH OF STALINISM IN BOHEMIA

KONEC STALINISMU V ČECHÁCH

THE DEATH OF STALINISM IN BOHEMIA

KONEC STALINISMU V ČECHÁCH

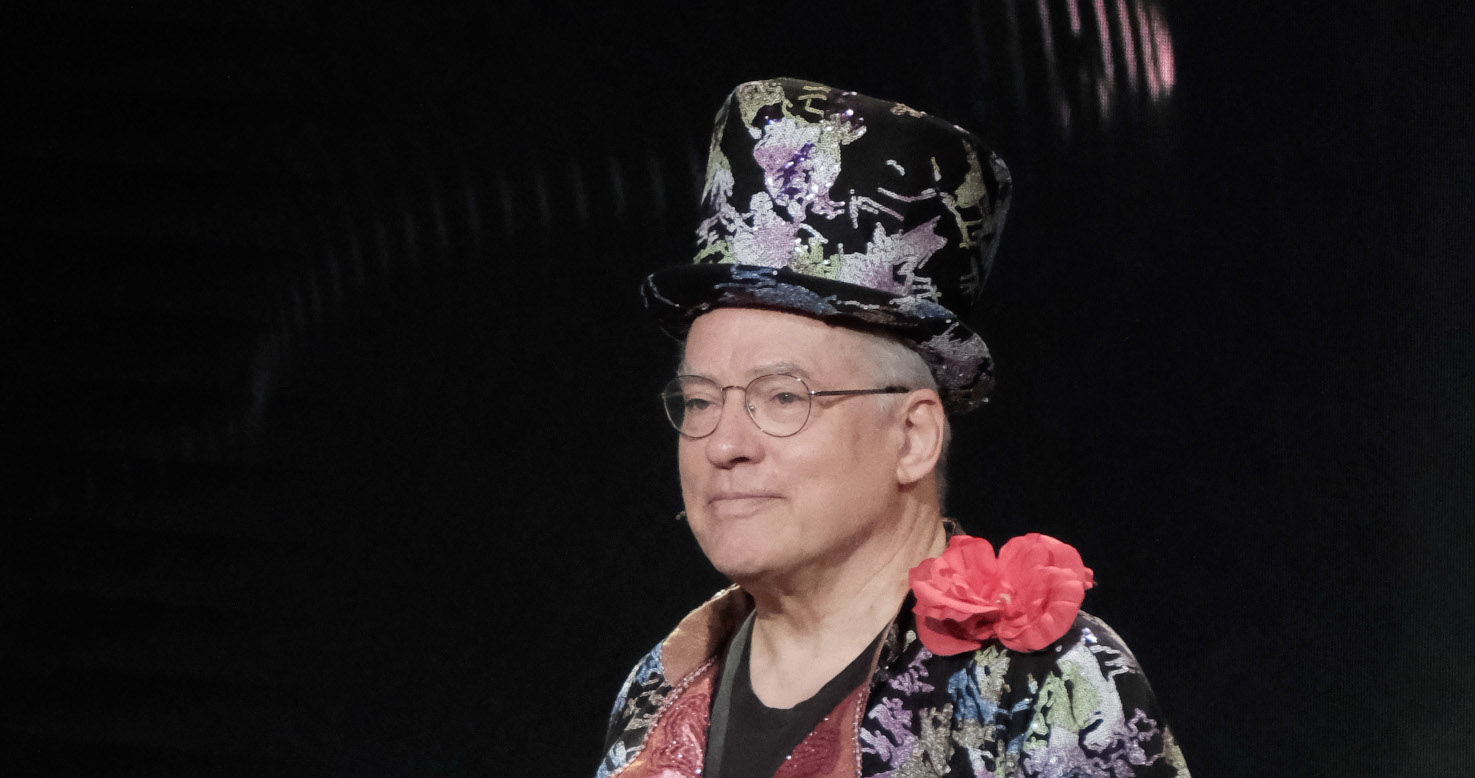

DIRECTED BY Jan Švankmajer

1991

Czechoslovakia

Jan Švankmajer, the master of Czech surrealism and animated film (Prague, 1934) made a substantial part of his subversive work during – and in opposition to – the communist period. Known for his distinctive stop-motion technique, his surreal and nightmarish visions as well as his dark sense of humor, Švankmajer continued to be productive after the Velvet Revolution in his own fiercely independent way. THE DEATH OF STALINISM IN BOHEMIA is without a doubt his most explicitly political film – Stalin’s bust finds itself on an operating table and is cut open to reveal the inner workings of Czechoslovak history between 1948 and 1990, as seen by Švankmajer who finds cruel, plastic and striking images for the communist period. The filmmaker himself would probably not be happy with our choice here: THE DEATH OF STALINISM IN BOHEMIA was commissioned in 1990 by the BBC, who asked Švankmajer to make a film about the situation in Czechoslovakia. Švankmajer later remarked: “Despite the fact that this film emerged along the same path of imagination as all my other films, I never pretended that it was anything more than propaganda.” Still, both as an introduction to Švankmajer’s work and a reflection on the transitional period in Central and Eastern Europe, it feels adequate that this animated film should be the first title of our (chronological) list. (hg)

ORANGE VESTS

ORANZHEVYE ZHILETY

ORANGE VESTS

ORANZHEVYE ZHILETY

DIRECTED BY Yury Khashevatsky

1991

Belarus/Germany

During the collapse of the Soviet Union, Belarusian director Yuri Khashevatsky assembled a group of female film students, among them Ella Milova and Irina Pismennaja, and encouraged them to make a collective documentary about the state of their country, seen from a woman’s perspective. Inspired by feminist artist collectives from East and West Germany the resulting film is as unique as it is harsh – a kaleidoscope of USSR life, depicting a militarised state in decay, in which women are at the forefront of fighting injustice, environmental problems and discrimination. Written as a cinematic letter to German feminist filmmaker Helke Sander, ORANGE VESTS offers a rare feminist perspective on the Soviet Union and the first years of its transition. At the time the film found distribution in Western Europe, but has since been largely forgotten. (hg)

GORILLA BATHES AT NOON

GORILLA KUPUJE POD

GORILLA BATHES AT NOON

GORILLA KUPUJE POD

DIRECTED BY Dušan Makavejev

1993

FR Yugoslavia/Germany

This is the final feature-length film by the legendary Yugoslav-Serbian director Dušan Makavejev. With his characteristic humor and cinematic inventiveness, it explores the fate of a Cold War soldier caught in a political and geographic no-man’s-land. The techniques of Serbian cutting – a radical style of montage that Makavejev initiated some 30 years prior – are on full display in this film, as is the director’s characteristically madcap sense of humor. A little-known fact is that the production of this feature was arranged by legendary filmmaker Želimir Žilnik, who got his start as an assistant to Makavejev in the 1960s, thus bringing the two legends of Yugoslav film full circle. (gdc)

BEFORE THE RAIN

PRED DOŽDOT

BEFORE THE RAIN

PRED DOŽDOT

DIRECTED BY Milcho Manchevski

1994

Republic of Macedonia/UK/France

Made in response to the throbbing and painful reality of the Yugoslav succession wars – as if in anticipation of the atrocities that were still to come – Milcho Manchevski’s BEFORE THE RAIN proved to be a visionary film in that it predicted the violence that was to grip the world far beyond the quaint village where part of it takes place. A weary cosmopolitan war photographer, burdened by the violence he has been witnessing without taking sides, is returning to his native Macedonia. Just days earlier he has experienced a mindless scuffle followed by a terrorist shooting at a London restaurant. Back home, he is faced with the impenetrable demarcation lines of religion that run through local silent animosities and prejudices. Magnificent Lake Ohrid and the remote mountain villages nearby have gradually fallen into the grip of a silent stand-off and unspoken intolerance. In a way, the film illustrates Samuel Huntington’s theory from ‘Clash of Civilisations’ in that it depicts a deadlock between Orthodox Christianity and Islam in the Balkans. It is permeated by sadness, which comes through the beautifully crafted images and symbiosis of music and sound, leaving the feeling of an impasse. Arranged in three parts with an elliptic and slightly overlapping time structure, BEFORE THE RAIN fascinates by challenging the viewer to place the events in a magical realist chronology. (di)

ACCUMULATOR 1

AKUMULÁTOR 1

ACCUMULATOR 1

AKUMULÁTOR 1

DIRECTED BY Jan Svěrák

1994

Czech Republic

The future Oscar winner Jan Svěrák at his experimental best. A fantastical story of unexplainable fatigue caused by television as a monster that sucks energy out of the main hero. His avatar lives in the mediated television universe. It is a playful, ironic take on Hollywood action films that flooded Czech movie theaters after 1989 and were both admired and looked down upon by domestic filmmakers. The energy of the 1990s newly “free” cinema where everything seemed possible is echoed in stream of formal innovations. Svěrák marries action film tropes, figures, and Spielbergian melodramatic touch with ironic esprit of the 1980s humanistic comedies penned by his father Zdeněk. ACCUMULATOR 1 is a film that leads – like its hero – a double life. That of a commercial film doubling as an existential contemplation on how not to lose touch with reality and not to amuse ourselves to death. (jb)

SATANSTANGO

SÁTÁNTANGÓ

SATANSTANGO

SÁTÁNTANGÓ

DIRECTED BY Béla Tarr

1994

Hungary

A black and white story of a rundown collective farm in a Hungarian village, SATANSTANGO stretches majestically over seven hours, and contains only around 150 shots, according to the director Béla Tarr. Tarr has established himself as a truly unique director because of his ability to prove that time in cinema is completely relative – just an instrument that can be bent to the author’s will. Nowhere is it more glaring than in SATANSTANGO which plays a bit like a thriller despite its exorbitant running time, and manages to captivate the audience in a trance, once the viewers have surrendered to the film’s tempo, long takes and slow zooms.

Like many of his works, it is based on László Krasznahorkai’s novel. The film’s composer and screenwriter Mihály Vig is also in one of SATANSTANGO’s lead roles as Irimiás. SATANSTANGO is a grand opus of Tarr’s impressive and unique filmography, a distillation of many of Tarr’s characteristics, and a piece of art that will only rarely be forgotten after viewing. (tp)

TITO AMONG THE SERBS FOR THE SECOND TIME

TITO PO DRUGI PUT MEĐU SRBIMA

TITO AMONG THE SERBS FOR THE SECOND TIME

TITO PO DRUGI PUT MEĐU SRBIMA

DIRECTED BY Želimir Žilnik

1994

FR Yugoslavia

A film that should absolutely be in the documentary canon for its bold interventionist strategies and daring psychological assessment of the post-socialist/post-war hangover is TITO AMONG THE SERBS FOR THE SECOND TIME. Tito rises again and takes a stroll through the city of Belgrade to determine what happened to his beautiful country and its upright young pioneers. What results is a canny assessment of the horrors of the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, catalogued in real time, as seen by those directly affected. Žilnik calls this work a happening more than a film, and so one can also situate it in the tradition of performance art and its documentation. Rarely has a video camera been used more effectively as a scalpel to peel back the layers of a society. (gdc)

BROTHER

BRAT

BROTHER

BRAT

DIRECTED BY Aleksei Balabanov

1997

Russian Federation

Danila (Sergei Bodrov) returns from the Chechen war in post-Soviet Russia, only to find that the world has moved on, moral values haven been exchanged for petty cash, and on the streets the principle of the survival of the fittest rules. Danila feels at odds with this new world, but adapts quickly, putting his military training to criminal use.

BROTHER is a film very much characteristic of its times – the early days of robber capitalism in 1990s’ Russia. Danila is a throwback masculine character of the Old World, a classic Western figure, but depicted with grace and empathy. BROTHER is very much like life in Russia at that time must have been – a fragmented world that offers strange, enlightening encounters and eruptions into sudden bursts of violence, and an examination of the beginnings of the new morals that the newly-found and newly-embraced market economy was founded on in Eastern Europe at that time. The visceral energy of the film is still undeniable, and the outdated values can be examined under closer scrutiny, now that they have become more aligned again with today’s more conservative Russia. (tp)

KHRUSTALYOV, MY CAR!

KHRUSTALYOV, MASHINU!

KHRUSTALYOV, MY CAR!

KHRUSTALYOV, MASHINU!

DIRECTED BY Aleksey German Sr.

1998

Russian Federation/France

Up to this very day, KHRUSTALYOV, MY CAR! remains one of the very few Russian cinematic attempts at dealing with Stalinist repressions in a comedic form.

Aleksei German Sr. depicts the Soviet Union in 1953 as a madhouse – the film is as claustrophobic as it is Kafkaesque; its pitch black humor is certainly not everybody’s cup of tea – at the Cannes premiere a great number of professional movie-goers left the cinema. The film deals with a great number of taboo topics – both explicitly and indirectly – such as the anti-Semitic doctor’s conspiracy in the Soviet Union, the horrors of communal living in shared apartments, the death of Stalin as well as the use of forced hospitalization on fabricated diagnoses of mental illness as well as rape in the Russian penal system. The title is taken from a sentence spoken by Stalin’s head of the KGB, Lavrenti Beria, who has a small role in the last part of the film. Despite the bleakness, comedy can be found in the film’s details – gestures, slapstick, costumes and a wild flood of dialogue, often pronounced by the actors all talking hysterically and at the same time. Describing the storyline seems futile – this film is more of an immersive experience into the extremities of Soviet life. A film like this would hardly be made again today – Armando Ianucci’s American-British comedy THE DEATH OF STALIN was banned from Russian cinemas in 2019 – but back in the „wild nineties“ censorship had not yet taken hold and a film like this was still possible – although extremely hard to finance. It took the director seven years to finish the work, which is nowadays considered a classic of 1990’s Russian cinema. (hg)

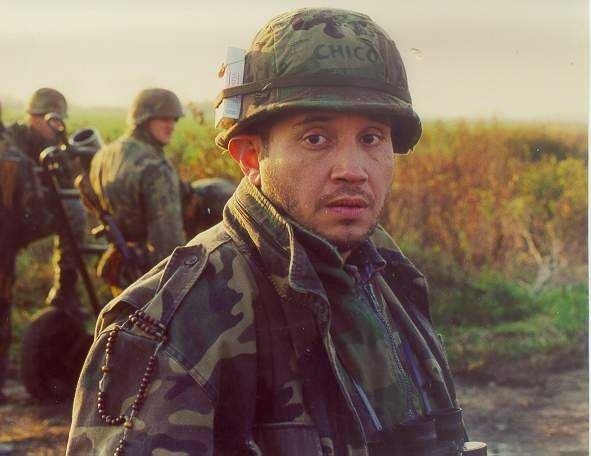

CHICO

CHICO

DIRECTED BY Ibolya Fekete

2001

Hungary/Germany/Croatia/Chile

A hybrid film or a re-enacted documentary, Ibolya Fekete’s CHICO is a complex biopic of a disoriented protagonist who clings to lofty ideology whilst opportunistically taking on the circumstances that life hurls his way. Set on either side of the crucial historical watershed often referenced as ‘the end of history’, it chronicles the life of a flamboyant and controversial personality, Bolivian-Hungarian Eduardo Rózsa Flores (1960–2009), nicknamed Chico. Feeling endlessly accountable to his father, a Latin American leftist intellectual, he is a larger-than-life transnational idealist, a pious revolutionary, who, like a chameleon, would embrace any political cause that meets his personal needs for action and faith – from assisting international terrorism to fighting as a mercenary for radical causes. At one moment he is a child witnessing Pinochet’s coup in Santiago, later on a state security agent in communist Hungary, then a media reporter turned Catholic guerrilla in the Croatian war of independence, and then a worshipper at the wailing wall in Jerusalem. From beginning to end, the film builds on a series of code-images and often distressing archival footage, from Bolivia, Chile, Hungary and Croatia. Amidst history’s upheavals and crumbling systems, CHICO is consumed by the ideological intensity that marked the political battles of the twentieth century. (di)

NIKI AND FLO

NIKI ARDELEAN, COLONEL ÎN REZERVA

NIKI AND FLO

NIKI ARDELEAN, COLONEL ÎN REZERVA

DIRECTED BY Lucian Pintilie

2003

Romania/France

Two neighbouring family apartments in Bucharest become the site of a post-socialist microcosm in Lucian Pintilie’s NIKI AND FLO. It all revolves around the marriage of the young daughter and son of the two families, who plan on emigrating to America soon after; their baby will be born a US citizen, and all preparations are taking place in front of a large wallpaper-poster showing the World Trade Centre towers. It is the clashes between the fathers-in-law, however, which are the center of attention: each one of them represents a specific post-socialist type of belief and behaviour: Niki Ardelean used to be a colonel and a communist party member. Everything in his world is collapsing; he cannot possibly reconcile with the re-writing of recent history he witnesses all around; his wife is drifting into docile dementia and his daughter is leaving. Florian Tufaru, on the contrary, is thriving. Under communism he made a living on the margins as a wheeler-dealer; he is cheerleading the nationalist reassessment of the past and encouraging the young to seek a better life in the West. And, he is clearly much better equipped for the new times ahead. The scuffles of the two grow over time, and so does Niki’s powerlessness. On the day of the young couple’s departure, it turns into an outburst of uncontrollable anger. Based on a true story, NIKI AND FLO shows a real drama of post-communism, reminding that there were many who believed in communism, there was no full consensus over the changes and that nostalgia for communism was sometimes borne out of anger and aggression. (di)

RUSSIAN ARK

RUSSKIY KOVCHEG

RUSSIAN ARK

RUSSKIY KOVCHEG

DIRECTED BY Aleksander Sokurov

2003

Russian Federation/Germany

A fictional grand tour of the Winter Palace of the Russian State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg takes us through 33 rooms and 300 years of the city’s history. Guided by a narrator (director Aleksander Sokurov himself) and his companion, we are introduced to a host of historical characters and situations.

RUSSIAN ARK is mainly appreciated for several technical aspects that make it unique among films. It is one of the world’s first full-length one-shot films – filmed as a one continuous long take of 87 minutes. Engaging over 2000 actors, it became a cinematic masterpiece that is held in high regard amongst art-house audiences.

The film’s central dichotomy between the Russian narrator and his European companion reflects the perpetual power struggle between the East and the West that has endured for many centuries, touching upon the theme of Russia’s national and cultural identity. With its visual opulence, the film is somewhat of an oddity in the director’s oeuvre. In recent years Sokurov has proven to be a skillful mentor for a new generation of filmmaking talents from diverse regions in the Russian federation: among them Kantemir Balagov and Kira Kovalenko. (tp)

CZECH DREAM

ČESKÝ SEN

CZECH DREAM

ČESKÝ SEN

DIRECTED BY Vít Klusák & Filip Remunda

2004

Czech Republic

These days Vit Klusák, Filip Remunda and their company Hypermarket Film are part of the most established Czech documentary elite. Their style: playfully provocative documentaries in which the filmmakers themselves often feature. CZECH DREAM was their graduation project in which they explore the Czech post-communist obsession with consumerism. The two film students dressed up in Hugo Boss suits, visited designers and advertising agencies and hired a composer for a theme song. Soon, dozens of professionals were working for the ‘Czech Dream’ – a brand new, remarkably cheap supermarket with bizarre advertising slogans, like: “Buy Nothing!” Thousands of Czechs turned up for the grand opening – only to find out that the store was just a facade in an empty field. Klusák and Remunda then went on to film the reactions of the public: plenty of people showed understanding for the artists’ intention and felt confronted with their own greed, but there was anger and disappointment as well. The film proceeded to travel the international festival circuit. With its critique of consumerism, CZECH DREAM managed to resonate with audiences world-wide. (hg)

GEORGI AND THE BUFERFLIES

GEORGI I PEPERUDITE

GEORGI AND THE BUFERFLIES

GEORGI I PEPERUDITE

DIRECTED BY Andrei Paounov

2004

Bulgaria

GEORGI AND THE BUTTERFLIES – along with other works of director Andrey Paounov (THE MOSQUITO PROBLEM (2007), THE BOY WHO WAS KING (2011)) and the acclaimed AGITPROP production company – documents the litanies of an individual faced with the difficulties of post-communist economic transition. It tells the story of incurable optimist and serial entrepreneur Dr Georgi Lulchev, who runs a care facility for the mentally ill in a village near Sofia, relying on a tongue-in-cheek humour, which makes it so convivial and watchable. In the 1990s, the facility is faced with a drastic cut in funding – one that affects social services after the end of state socialism. The occasional donations of clothing and expired medications that come via the newly opened diplomatic channels do not resolve the difficulties in a context where staff is laid off and the well-being of patients is left to chance. An idealistic and energetic personality endowed with a tireless entrepreneurial zeal, Georgi embarks on pursuing a series of business ideas that he hopes will make the care home self-sufficient and will sustain it for the future. The incurable optimism of the protagonist, his penchant for extravagant ideas (snails, nutria, ostriches, cocoons) all of which inevitably fail, the childlike vulnerability of the inmates and the spectacular mismatch between dreams and reality all contribute to a subtle comic effect. But it makes for a bittersweet viewing: a grotesque, uplifting, and ultimately very sad story. (di)

THE BLOCKADE

BLOKADA

THE BLOCKADE

BLOKADA

DIRECTED BY Sergei Loznitsa

2005

Russian Federation

Sergei Loznitsa is among Eastern Europe’s most productive directors and one who continues to deal with the darker pages of Soviet history. BLOCKADE is one of his first films which is completely assembled from archival materials and at the time broke the taboo of the heroic image of the Leningrad Siege during the Second World War. The importance of this war in the national consciousness, called the “Great Patriotic War” in the former Soviet Union, cannot be overstated. But in BLOCKADE, instead of displaying the victorious one-sided images of Soviet war films, Loznitsa changes the narrative by assembling original footage shot during the siege: the exhausted inhabitants of St Petersburg trudging through the snow, desperately searching for food. Frozen bodies line the streets. Reworked sound design makes the images even more immediate, as if they are set in the present. Loznitsa would repeat this effective method in many of his later archive films (STATE FUNERAL (2019), BABI YAR. CONTEXT (2021)) – it peels off the layers of propaganda and reduces the images to their human proportions – in this case the proportions of a deep tragedy that unfolded during the 16 months of the siege, between September 1941 and January 1943. (hg)

THE DEATH OF MR. LAZARESCU

MOARTEA DOMNULUI LĂZĂRESCU

THE DEATH OF MR. LAZARESCU

MOARTEA DOMNULUI LĂZĂRESCU

DIRECTED BY Cristi Puiu

2005

Romania

Dante Lazarescu, the eponymous protagonist of THE DEATH OF MR LAZARESCU, is a man in his sixties, quite worn out for his age. He lives alone in an unkempt apartment and is known to drink a lot. One evening he feels ill and, as the film’s title reveals, dies before dawn. Perennially deteriorating, he spends most of the night in an ambulance which drives him around different hospitals in Bucharest where the emergency nurse, Mioara, is trying to get him admitted, or at least to get the tests and attention he needs. In vain. The doctors one encounters in the course of the night – gatekeepers of modern medicine’s tool of assistance – range from self-protective bureaucrats to indifferent cynics. As Lazarescu gradually loses consciousness, the nurse is his only advocate left with any empathy, a trusted figure who accompanies him through the descending cycles of hell. On the surface this is a film about the administrative nightmare of a healthcare system in crisis. Underneath, however, it is about a society that has run out of compassion and has found itself in the grip of institutional corruption and moral decline, an existentialist film in which a single individual is let down by the profound rupture in all human support networks. Underpaid and underappreciated, doctors are demoralised. And not much has changed since 2005: there are shiny pharmacies on every corner in the cities and politicians make self-congratulatory speeches on advances in healthcare. Yet the ordinary elderly fear entering a hospital more than anything and would rather be left to die alone at home. (di)

12:08 EAST OF BUCHAREST

A FOST SAU N-A FOST?

12:08 EAST OF BUCHAREST

A FOST SAU N-A FOST?

DIRECTED BY Corneliu Porumboiu

2006

Romania

Corneliu Porumboiu’s 12:08 EAST OF BUCHAREST is a film that radically challenges the factors shaping personal and historical memory. It reveals the battle of narratives in the post-communist space. In that, it has significance far beyond the Romanian context. On the fifteenth anniversary of the 1989 Christmas uprising in Romania, which led to the demise of communist power that had persisted here for longer than in the other countries of the bloc, the host of a provincial live talk show on one of the newly emerged private TV channels is summoning two men – an alcoholic teacher and a retired janitor – to debate the question if there was a revolution in their town or not. It is an either-or proposition formulated quite simply: if there were protests earlier than 12:08 pm on 22 December 1989 (the moment Ceausescu ran away from raging crowds that booed him in Bucharest), it would mean locals in the town had overcome their fear and revolted independently: therefore, one could claim there was a courageous local revolution. Had, however, protests happened only after that crucial point in time, the town’s people would have simply been opportunistically reacting to the tide of protests elsewhere. So, was there a revolution in this town – east of Bucharest – or not? It comes down to judiciously reconstructing and examining individual behaviours. The talk show grows into a purposefully staged cross-examination, a courtroom drama of sorts staged for an imaginary jury of public opinion called to task by the show’s anchor. The various callers offer testimonials to the timeline, and some act as character witnesses for the unlikely protagonists of the local ‘revolution’. 12:08 EAST OF BUCHAREST is a textbook example of a study of memory and witnessing – and it shows how susceptible historical interpretations are to master narratives that trump and shape personal recollections. (di)

GRBAVICA: THE LAND OF MY DREAMS

GRBAVICA

GRBAVICA: THE LAND OF MY DREAMS

GRBAVICA

DIRECTED BY Jasmila Žbanić

2006

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Grbavica is a neighborhood in Sarajevo, and the setting for Jasmila Zbanić’s feature fiction debut, which won her the Golden Bear in 2006. Single mother Esma believes hat revealing the truth about the identity of her daughter Sara’s father would damage both her and her child: Esma got pregnant after she was raped during the Bosnian war. It is estimated that ca 20,000 Bosniak women were systemically raped by Serbian troops. The film tackles the taboo topic head-on and offers hope for the possibility to survive after trauma. The female experience of and perspective on war is a topic that runs through Zbanić’s entire oeuvre – her own films and those produced by Deblokada, the production outlet and artists’ collective she founded in 1997, take an explicit political stance and focus on social issues in the region. (hg)

RENÉ

RENÉ

DIRECTED BY Helena Třeštíková

2008

Czech Republic

René is a small-time crook in and out of prison, constantly defying the social order and living in complete disregard for himself, his life, or people around him. He is one of many. What makes him unique is the fact that in the film named after his character, we observe his development over two decades, during which he witnesses such cataclysmic events as the Velvet Revolution, 9/11 and the Czech Republic’s admittance to the European Union.

Since the mid-noughties, Czech documentarist Helena Třeštíková has established herself as a singular voice in documentary filmmaking with a series of so-called latitudinal documentaries that follow their main subjects for an extensive period of time, usually spanning several decades. RENÉ is a prime example of this approach, trading familial relationships for outsider political comment, and presenting a very unlikely (anti) hero who represents the age of his rough journey. (tp)

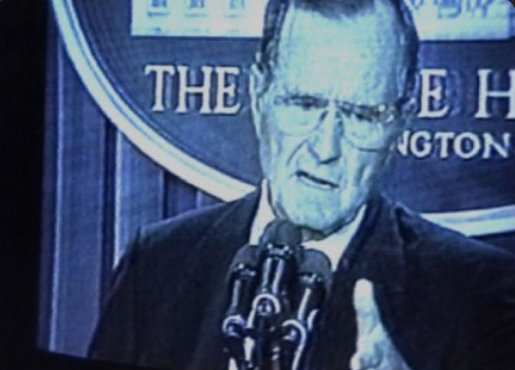

LITHUANIA AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE USSR

LITHUANIA AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE USSR

DIRECTED BY Jonas Mekas

2009

USA/Lithuania

“This video is made of footage that I took with my Sony from the television newscasts during the collapse of the USSR, with noise from home in the background. It’s a capsule record of what happened …” writes Jonas Mekas about his own film. And that’s what it is: In the early hours of January 13, 1991, hundreds of Lithuanians headed to the TV tower in Vilnius, where they would make a stand against Soviet troops deployed to crush the Baltic state’s bid to reclaim independence. More than a dozen died, and hundreds were wounded. These tragic events ultimately contributed to the collapse of the entire Soviet Union. From afar in the US, his adopted homeland for many years, Lithuanian filmmaker and avant-garde pioneer Mekas watched the news of the USSR’s collapse on American TV. The resulting film is as simple as it is experimental: Mekas started filming the news from his television screen and edited a film out of this material – thus the events in Lithuania appear through two filters: that of the American news and that of the auteur filmmaker with his Sony video camera. The result is a meditation on the demise of an empire, on a split screen, with “noise from home in the background”. (hg)

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF NICOLAE CEAUȘESCU

AUTOBIOGRAFIA LUI NICOLAE CEAUȘESCU

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF NICOLAE CEAUȘESCU

AUTOBIOGRAFIA LUI NICOLAE CEAUȘESCU

DIRECTED BY Andrei Ujică

2010

Romania

Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu was obsessed with the medium film – all of his (foreign) travels, state events and visits of high “friends” from abroad were meticulously documented and kept for generations to come. Thus, in a way, Ceaușescu himself turns out to be as much the author of this documentary as the director, Andrei Ujică, who selected the film from more than 1,000 hours of filmed state propaganda, official news reports and home movies.

The film starts with raw VHS footage of a trial – filmed shortly before the dictator and his wife were executed after the Romanian Revolution in 1991. These dark and grainy images are a stark contrast with the pomp and parades that follow. For decades, beginning in 1965, the Ceaușescus ruled Romania with an iron fist. It’s baffling to see how world leaders even in the West rolled out the red carpet for the dictator – the Queen of England received him with pomp and circumstance. But the devil lies in the details: while the Queen and Ceaușescu enjoy a ride through the London high streets in an open carriage, a porn movie theatre with DEEP THROAT (1972) on the program, prominently appears in the background of the frame. Did the camera person film it on purpose? We will never know. The bizarre visit to North Korea in the film seems more in line with what we know about Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena today. The rise and fall of a dictator made from his own images. (hg)

WINTER, GO AWAY!

ZIMA, UKHODI!

WINTER, GO AWAY!

ZIMA, UKHODI!

DIRECTED BY Elena Khoreva, Denis Klebleev, Dmitry Kubasov, Askold Kurov, Nadezhda Leonteva, Anna Moiseenko, Madina Mustafina, Sofia Rodkevich, Anton Seregin & Alexey Zhiryakov

2012

Russian Federation

During “Maslenitsa”, a Slavic holiday with pagan roots, a straw puppet is set on fire while the words “Winter, go away!” are repeated several times. With this tradition Russians celebrate the end of winter, welcoming springtime and the beginning of new life. German documentarist Helke Misselwitz already used the expression in the title for her classic documentary (WINTER, ADÉ! (1988)) about life and hopes in the last years of the German Democratic Republic. In the Russian collective documentary included in our list here – a work which was filmed and edited by 11 students from the Moscow-based documentary school of groundbreaking documentary filmmaker Marina Razbezhkina – events around the protests leading up to the Russian presidential elections in 2012 are shown from different perspectives in Russian society. More than 1,000 hours of footage shot by the young filmmakers was seamlessly edited together into an 88-minute film. This emphasises the fact that the students were working under the same set of aesthetic prescriptions which asserts the efficiency of Razbezhkina’s method as a filmmaker and teacher. Opposition figures from different ideological backgrounds – among them Boris Nemtsov, Eduard Limonov, Gary Kasparov, Alexey Navalny and oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov – appear both in public and private, oftentimes quite intimate settings, alongside human rights activists, the punk band Pussy Riot and Russians from all age groups and various walks of life, expressing their opinions and their need for self-determination freely. The film forebodes not the end of winter, but rather a new era of state oppression. It is hard to watch this film in 2021: the last scenes show police violence, unlawful arrests and increasingly disillusioned opposition members. WINTER, GO AWAY! is a film like a time-capsule – interesting not only because of its topic but also because of its formal aspects and the fact that many of the contributors went on to have prosperous careers as documentary filmmakers in their own right. (hg)

THE BURNING BUSH

HORÍCÍ KER

THE BURNING BUSH

HORÍCÍ KER

DIRECTED BY Agnieszka Holland

2013

Czech Republic/Poland

Director Agnieszka Holland is well-known for her historical films covering some of Eastern Europe’s darkest chapters. But she is also one of the first filmmakers in Central and Eastern Europe to truly embrace and pioneer in the serial format. THE BURNING BUSH combines both: it was originally written and shot as a mini-series and later edited into a feature film. The story focuses on the events surrounding Jan Palach’s self-immolation in 1969 out of protest against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. The series’ format gives room to both extensive character development and a depiction of the political and social context of the time. (hg)

IN BLOOM

GRZELI NATELI DGEEBI

IN BLOOM

GRZELI NATELI DGEEBI

DIRECTED BY Nana Ekvtimshvili & Simon Gross

2013

Georgia/Germany/France

Two girlfriends, Eka and Natia, abruptly come of age in 1992, in Tbilisi, Georgia, when they try to break free from rigid social structures and stifling familial ties. Their plight reflects the aspirations of Georgia on the threshold of a new era, having just broken away from the Soviet Union and destined to forge its own path. The re-emergence of Georgian cinema in the 21st century has been spectacular, and IN BLOOM is a prime example of how wise management of resources, paired with the trademark of Georgian poetic approach and good storytelling can result in a film that feels new and fresh, and successfully captures a turbulent, wild moment in Georgian history on the big screen.

IN BLOOM offers vibrant characters and sharp social commentary, and its message of female empowerment in a conservative cultural setting paved the way for many similar sentiments and movements of today. (tp)

JUDGEMENT IN HUNGARY

JUDGEMENT IN HUNGARY

JUDGEMENT IN HUNGARY

JUDGEMENT IN HUNGARY

DIRECTED BY Eszter Hajdú

2013

Hungary/Germany

JUDGEMENT IN HUNGARY is a chamber piece documenting a historical court case which started in March 2011, and ended in August 2013 in Budapest. The 167 days of hearings were documented continuously by documentary filmmaker and activist Eszter Hajdú and her crew. The defendants on trial: Hungarian right-wing extremists who were accused of committing a series of premeditated attacks on members of the Roma community. Six people were killed, including a five-year-old, and another five were injured. JUDGEMENT IN HUNGARY traces the fate of three Roma families who trust the judicial system to give them closure. They believe that justice will be served and trust that the Hungarian state will protect them. But over the course of the film it becomes more and more questionable whether the extremists will be found guilty. The widespread anti-Roma sentiment in Hungarian society, and the contradicting statements from the police give one reason to fear they will not. Despite the fact that the film was made with modest means, the result is a harrowing and impactful must-see documentary. (hg)

LEVIATHAN

LEVIAFAN

LEVIATHAN

LEVIAFAN

DIRECTED BY Andrey Zvyagintsev

2014

Russian Federation

Born in Novosibirsk, Andrey Zvyagintsev started out as an actor in off-theaters, before making his first feature-length film at the age of 38. This debut, THE RETURN (2003) won him the Golden Lion in Venice, international acclaim and inevitable comparisons to Andrei Tarkovsky, whose allegorical and enigmatic epics his work echoes. With ELENA (2011), his third feature, Zvyagintsev’s work started taking another, more political and socially engaged turn. The work, which most skillfully combines this social criticism with Mikhail Krichman’s classical 35mm cinematography, Oleg Negin’s scriptwriting and Zvyagintsev’s own fondness for deep characters and biblical stories, is LEVIATHAN. The film also gained him an Oscar nomination despite the fact that the Russian ministry of culture was declared to be “not impressed” by the pessimistic film which tells a tale of corruption, clericalism and provincial stagnation. Kolya lives with his wife and son from his first marriage in an idyllic house in the northern Russian countryside. A new, corrupt mayor tries to expropriate Kolya’s land and Kolya decides to fight this by hiring his friend Dmitri, a slick Moscow-based lawyer. Little does Kolya suspect that his life will change drastically and he is bound to lose everything when local authorities, the church and his own family all turn against him. A devastating film and a great work of art. (hg)

AFERIM!

AFERIM!

DIRECTED BY Radu Jude

2015

Romania/Bulgaria/ Czech Republic/France

Radu Jude has made several films that relentlessly expose the ugly and little-discussed nationalist and racist tendencies, found both in history as well as in present day (DEAD NATION (2017), I DO NOT CARE IF WE GO DOWN IN HISTORY AS BARBARIANS (2018)). In this line of work, AFERIM! has a special place, as it deals with matters related to the Roma, the most sizeable and vilified transnational minority ethnic group in the region.

The story is set in Wallachia, in the 1830s, and follows a bounty hunter and his son. They are in the footsteps of a Romani man, a runaway slave, who has escaped the estate after his affair with the boyar’s wife has come to light. The Romani, Carfin, is apprehended and hauled back, then publicly humiliated and castrated whilst his family members look on in shame. It becomes clear that it was not the Romani who pursued the lady of the house, but it was rather she herself, a frustrated consort, who reached out and summoned the slave to take care of her needs.

With its plot and execution, AFERIM! is important on two planes. First, it is a milestone in acknowledging slavery in the history of European Roma people – a fact that is little recognised and under-discussed in the official histories of the region. Secondly, it tackles matters contextually. It does not place the Romani protagonist in the center of the narrative but keeps him on the margins whilst focusing on the overall attitudes toward the Roma. This allows to reveal a culture of power that is structured around blaming the victim – Carfin is silenced, beaten and downtrodden, deprived of agency and yet treated as a fully-fledged subject who can be kept responsible and continuously punished. (di)

PAPUSZA

PAPUSZA

DIRECTED BY Joanna Kos-Krauze & Krzysztof Krauze

2013

Poland

At the center of this collaborative work of husband-and-wife team Joanna Kos-Krauze and Krzysztof Krauze is the problematic relationship of Romani poet Bronisława Wajs and Polish writer and resistance fighter Jerzy Ficowsky who found refuge with the Roma during the Second World War, and encouraged Bronisława, nicknamed “Papusza” (little doll), to write. During his stay with the Roma, Ficowsky learned the Romani language. He enabled translations into Polish of Papusza’s work – making her the first Romani poet to appear in Polish and one of the most prominent Romani poets worldwide. However, when Ficowksy published a work about his time in the Roma settlement, describing their language, myths and customs, Papusza was accused of betraying her people and banned from their ranks. The film, shot in striking black and white images, manages to avoid a romantic view of the Roma people while touching upon complicated topics like anti-gypsyism, the Roma holocaust and the position of women within the Roma community. (hg)

CLOSE RELATIONS

RODNYE

CLOSE RELATIONS

RODNYE

DIRECTED BY Vitaly Mansky

2016

Latvia/Estonia/Ukraine/Germany

Like many citizens born and bred in the USSR, renowned documentary filmmaker Vitaly Mansky is of mixed heritage: he was born in Ukraine but carries Russian citizenship. In CLOSE RELATIONS he travels across Ukraine to explore society after the Maidan revolution, as mirrored within his own large Ukrainian family. His relatives are spread all across the country: in Odessa, Lviv, the separatist area in Donbass, and in Sevastopol on the contested Crimea peninsula. The film investigates the reasons for the conflict, after which citizens of a single country found themselves on different sides of the barricades. In Russia, meanwhile, Ukraine has become a taboo topic. Vitaly Mansky is perhaps best known for his portraits of political leaders (PUTIN’S WITNESSES (2018), GORBACHEV. HEAVEN (2020)), but CLOSE RELATIONS is without a doubt one of the filmmaker’s most personal works. (hg)

THE OTHER SIDE OF EVERYTHING

DRUGA STRANA SVEGA

THE OTHER SIDE OF EVERYTHING

DRUGA STRANA SVEGA

DIRECTED BY Mila Turajlić

2017

Serbia/France/Qatar

THE OTHER SIDE OF EVERYTHING announced to the world the current renaissance in Serbian documentary, and the fact that women directors are leading this charge. A revelatory study of multi-generational political activism in a country still undecided between its past and future, the film won the top award at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, the most significant festival for non-fiction cinema in the world. Receiving this award, the torch has been passed on to a new generation of directors in the country who will write a new chapter in what has been an illustrious if yet underappreciated cinematic history. (gdc)