_UNDERSCORE

Cinema from Kalaallit Nunaat

Stories from Greenland, not just about it

_UNDERSCORE

Cinema from Kalaallit Nunaat

Stories from Greenland, not just about it

by Davide Abbatescianni

At a moment when Greenland is increasingly framed through the language of geopolitics, resources and strategic interests, the European Film Academy’s decision to dedicate a special _UNDERSCORE edition to Greenlandic cinema offers a different entry point: one grounded in stories, memory and lived experience. The selection, now available on the Academy VOD platform after the European Film Awards ceremony on 17 January, brings together landmark works spanning more than two decades of filmmaking, from the country’s first feature to recent, internationally acclaimed shorts and documentaries.

For Inuk Jørgensen, award-winning filmmaker, producer and consultant working out of Greenland, the initiative carries both symbolic and concrete weight. “For a very small and young film community it means a great deal to showcase anywhere in the world,” he explains, “but it is – for obvious reasons – very impactful for the Greenlandic film community to experience and feel the interest and support from larger communities like the European Film Academy.” The timing is significant: Greenland is in the process of establishing its first-ever film institute, a development that marks a decisive step in the long-term structuring of a national film ecosystem. As Jørgensen notes, the Academy “has been very supportive in the whole process of laying the foundation of a Greenlandic ‘film industry’.”

Cultural visibility and political context are inseparable here, even if cinema operates on a different register. “It goes without saying that it is a bit of both,” Jørgensen says. While the _UNDERSCORE platform offers much-needed international exposure for Greenlandic stories, it also aligns with the Academy’s broader commitment to filmmakers from minorities across Europe. Crucially, he adds, this is not simply about inclusion but authorship: “I think this shows not just a sincere interest in original storytelling but also original stories told by people who are from places that just 25 years ago were not able to tell their own stories through film.”

That distinction becomes particularly important in a media landscape where Greenland is often spoken about rather than listened to. Cinema, Jørgensen argues, can articulate what political discourse cannot. “Cinema speaks to a different set of sensibilities. Cinema has the power to move you, to transgress borders and carry what is most meaningful to all peoples – stories.” Seen together, the films selected for this edition trace the emergence of a cinematic voice alongside the formation of a nation-state. “They are not just stories,” he stresses, “but part of the canon of Greenlandic narrative sovereignty.”

The programme itself reflects this arc. NUUMMIOQ (2009), directed by Otto Rosing and Torben Bech, stands as the first Greenlandic feature film, a modest love story that nonetheless marked a turning point in representation and production. Inuk Silis Høegh’s SUMÉ: SOUND OF A REVOLUTION (2014), which premiered at the Berlinale, revisits the band whose music helped articulate a political and cultural awakening in the 1970s. More recent works, such as WALLS – AKINNI INUK (2025) and THE WHITE GOLD OF GREENLAND (2025), confront trauma, justice and the economic legacy of colonial structures, whilst shorts like ENTROPY (2024) and THE LAST GRASS SEAMSTRESS (2024) engage with climate, tradition and the fragility of inherited knowledge.

Taken together, the films offer a portrait that resists easy generalisation. “What the audience will meet are Greenlandic stories,” Jørgensen emphasises. “Stories from Greenland, and merely not about Greenland.” A key shift, he explains, has been the gradual move from externally framed narratives to works shaped by Greenlandic filmmakers themselves. “Since the very first Greenlandic short film, Inuk Silis Høegh’s GOOD NIGHT (1999), Greenlanders have been telling their stories in the media of film and gradually taken up a larger role in films told, by outsiders, about Greenland.” What makes this selection distinctive is the degree of creative control: all the films have Greenlandic directors or co-directors, and in several cases Greenlandic producers as well.

Recurring themes of memory, loss, colonial history and resilience are not coincidental, but rooted in lived reality. “It’s only a little more than 70 years ago that the colonisation – or modernisation – of Greenland really began,” Jørgensen notes, referring to the period when Greenland was formally absorbed into the Kingdom of Denmark. The rapid transformation that followed brought both material change and cultural rupture. “For many people this meant a loss of traditions and adapting to new ways of living,” he says. “Greenlandic cinema is a reflection of this contrast between the old and the new.”

Personal stories, in this context, become vehicles for collective memory. Drawing on Inuit oral traditions, Jørgensen points out that storytelling has long operated as a shared, communal process. “The Inuit of Greenland and elsewhere were an oral people,” he explains, and narratives naturally moved from individual experience to collective lore. Cinema, in that sense, becomes a contemporary extension of an older practice, translating stories of trauma, family and community into a new medium while preserving their social function.

Despite growing international recognition, Jørgensen is clear-eyed about where Greenlandic cinema stands today. “Yes, Greenlandic cinema is still finding its feet,” he says. The domestic audience remains crucial: screenings take place not only in the country’s two cinemas but also in community halls along the coast, often attracting a large proportion of the local population. At the same time, the past decade has seen a noticeable international breakthrough, with films premiering at major festivals and winning awards abroad. In a small film community, such successes resonate widely. “When one filmmaker or a group of filmmakers has success in getting a Greenlandic film out into the world it benefits the whole community,” Jørgensen observes. “It creates a spotlight on us all.”

In that light, the Greenland edition of _UNDERSCORE is more than a curated programme. It is a gesture of trust, solidarity and recognition at a moment when Greenland’s voice risks being overshadowed by louder geopolitical narratives. By foregrounding cinema as a space of self-definition and narrative sovereignty, the European Film Academy offers audiences not a commentary on Greenland, but an invitation to listen.

Partners:

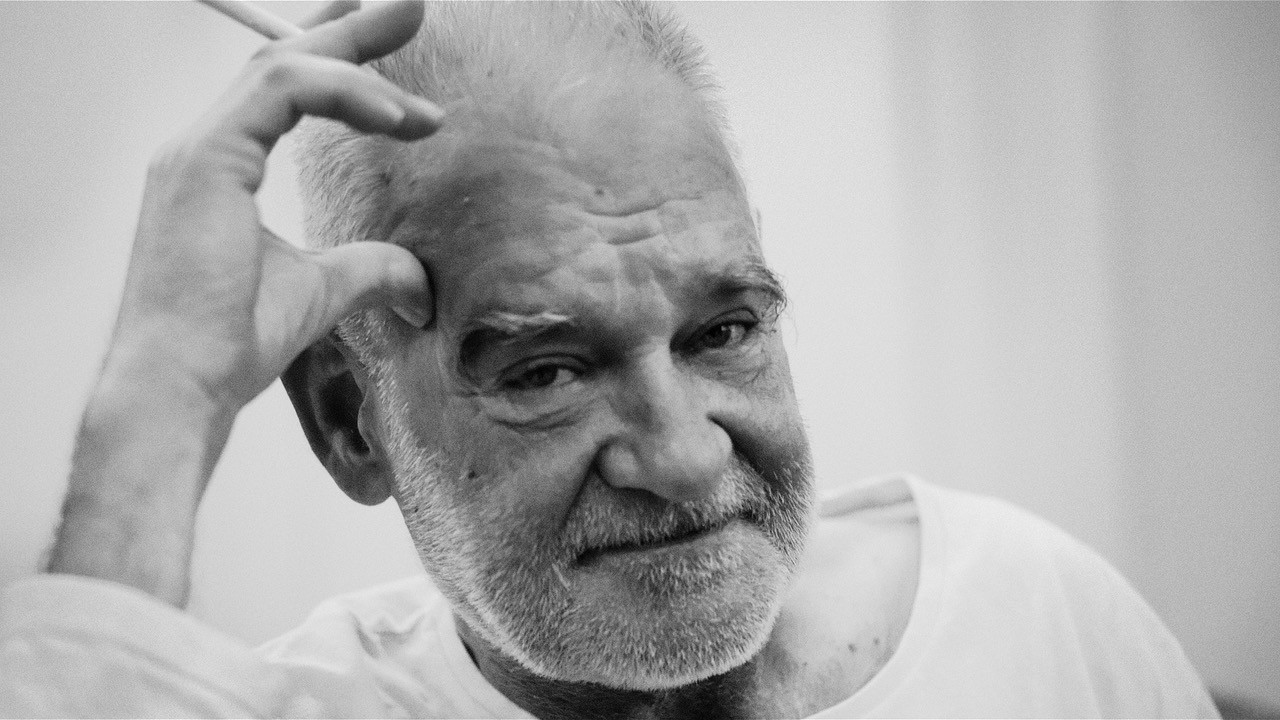

Davide Abbatescianni

Davide Abbatescianni

Davide Abbatescianni is an Italian film critic and journalist. After studying theatre, film and journalism in Italy, Estonia, and Ireland, he began working as a reporter for Cineuropa in 2017, covering major festivals and markets. His articles have appeared in publications such as Variety, The New Arab, New Scientist, Business Doc Europe, and The National. He is a member of FIPRESCI and the European Film Academy. He is also a curator for the Support to EU Film Festivals project. He is currently based in Rome.

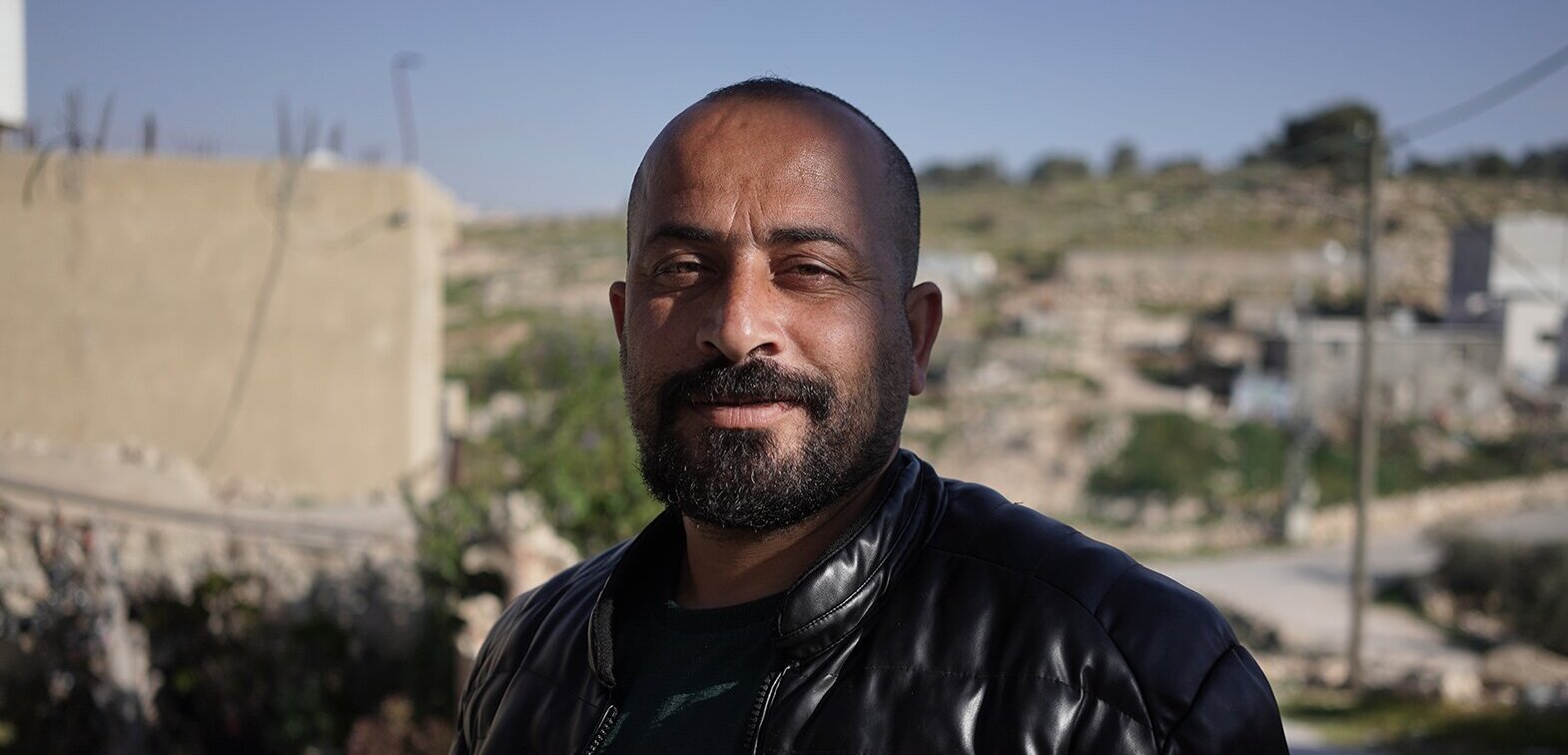

Inuk Jørgensen

Inuk Jørgensen

Wildscreen selected-/ Earth day Network nominated filmmaker based in Sweden but mostly working out of Greenland. Voting member of the European Film Academy, board member of Film.GL, EAVE Producers Workshop graduate, EFM Toolbox alumni, head of Nordiska Filmskolan, Master of the Arts in Film and Language, experienced in marketing, teaching, and lecturing.

Film Institute of Greenland

Film Institute of Greenland

The Film Institute of Greenland started operating in the biginning of January 2026. The film institute is thus still in the process of setting its frames. The CEO is Inunnguaq Petrussen. For general requests e-mail film@nanoq.gl